For some time, the fate of Audi seemed sealed. Post World War II, Auto Union GmbH’s production was focused on the DKW automobiles that fit into the European economic situation much better than the pre-War luxury cars from Horch and Audi. But the market was changing, and Auto Union launched the very pretty 1000SP Coupe and Convertible. But, there was no denying that the 1000SP looked like a 1950s car in a 1960s world. Audi’s production would really have to wait until the launch of the C1 chassis in 1968; prior to that, some re-badged DKW models wore the Audi name but sold only in small numbers. The C1 would prove to be a pretty popular model, though, and the new 100 model would be available as both a sedan and as a 2-door “Coupe S” model. The lines of that model, as with the 1000SP, mimicked more expensive and famous cars such as the Fiat Dino and Aston Martin DBS. It was a pretty large departure from the mini-Thunderbird look of the 1000SP and much more modern. But, it appears that there may have been a missing link developed in the mid-1960s:

Category: DKW

The world of Auto Union is full of paradox. That the company even came into existence is itself somewhat of a fluke, but a harsh economic situation in Germany in the 1930s led four mostly failing companies to band together in the hope that united, they might survive. Out of that union was born the image of the four rings that today are worn proudly by the last remnant, and the least successful, of the original four – Audi. If that isn’t strange, the history of how we got to that point certainly is. Only one of the companies was truly successful when they banded together, and they produced primarily motorcycles, not cars. Yet only one year after being founded, the fledgling company put its technical prowess up against the might of the most storied car company in the world – indeed, the inventors of the automobile – Daimler-Benz. And by “its” technical prowess, I mean the technical prowess of one Ferdinand Porsche, himself an outcast of sorts from several car companies. His design was both unorthodox and unusual, with a single-cam supercharged 16 cylinder engine mounted in the middle of the car. Mind you, this was a full 25 years before Cooper would make the “revolutionary” change that would be the accepted practice of all modern Formula One cars. With entirely new suspension designs and strange handling behaviors – never mind enough torque to jump start an industrial production line and tires that would consequently disintegrate immediately or fuel that was really just a high explosive in liquid form – the Auto Union Grand Prix cars shared nothing in common with the road-going models marketed by the company, who at the start of the 1930s didn’t even produce what could loosely be identified as a sports car.

Yet, it worked.

Auto Union may numerically have not won as many races as Mercedes-Benz did over the same period, but they established themselves on the same level – no small feat, considering the company. They won races, championships and set records and were primed with new luxury, smart economy and even sports vehicles to capitalize on their great success at the race track and in the record books. And then, World War II broke out, and as fate would have it Auto Union’s primary headquarters were in Saxony. For those of you who aren’t particularly fond of maps, Saxony happens to be exactly where the Russians ended up advancing into in 1945. Mired in what would become East Germany, there didn’t appear to be much hope for Auto Union and it seemed they were relegated to the history books. But in 1949 the company was relaunched, now based in Ingolstadt – not far from its old rivals. The brand that had previously been the bread and butter of Auto Union’s sales – DKW – would carry the four rings and continue to make economy cars, but little else remained from the former glory of Auto Union. Indeed, even DKW itself was full of contradictions; the name derived from “Steam Powered Car” in German (Dampf-Kraft Wagen), yet the company hadn’t produced a steam car since the late teens. Their current lineup continued the strange trend with oxymoronic names like “3=6”. Math not being their strong suit, DKW alternatively called the car F900, F91, and finally “Sonderklasse”, though there was no longer a non-Sonder model. The underpinnings would make Swedes smile, with a two-stroke inline-3 powering the front wheels. And from these modest bones the only officially badged “Auto Union” was created – the 1000SP. With a bit more power and styling borrowed from an American classic, it was a special car:

CLICK FOR DETAILS: 1961 Auto Union 1000SP Coupe on eBay

2 Comments

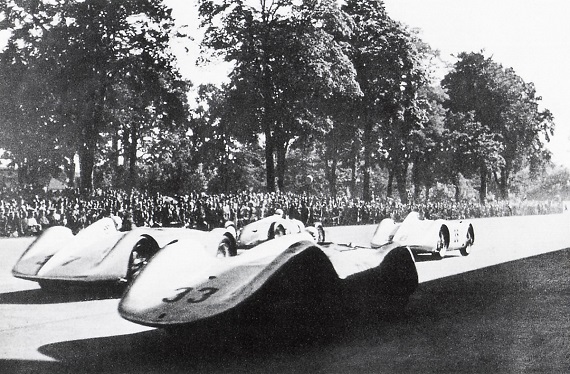

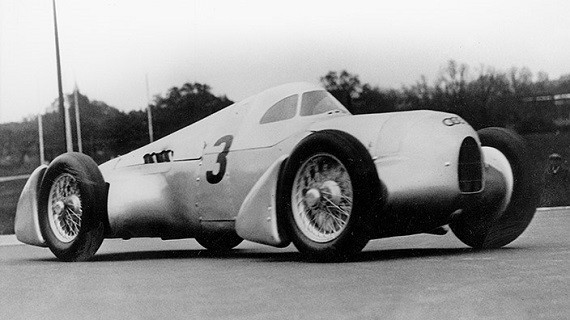

A 1935 Auto Union Type B Streamliner used for both records and the annual Avus race in Berlin

This past weekend weekend we saw a bit of hubris and bad strategy lead to Mercedes-Benz losing to Ferrari in the Malaysian Grand Prix. Despite the massive investment and seemingly pedantic attention to detail, the same problems existed in the 1930s for the company. Increasingly Mercedes-Benz needed to differentiate itself from Auto Union by undertaking extreme efforts. These efforts were not always profitable; indeed, one could argue that – as we saw last week – since they were already having difficulty delivering cars thanks to raw material shortages, undertaking new forms of racing and record-breaking might have seemed ill-conceived for the company. However, still at stake was preferential treatment from the government, especially when it came to lucrative military contracts. As such, Mercedes-Benz undertook some unlikely projects to not only gain international prestige for the Daimler-Benz model range, but indeed to curry favor with the government.

FOUR : PUSHING THE LIMITS – THE GOVERNMENT GOES RACING

A Mercedes-Benz W125 leads an Auto Union Type C – the height of power for these Grand Prix cars in 1937 As we’ve seen in…

Comments closedEntering the world of historic racing in general is not something that can be terribly easily achieved, but when you start talking about historic Porsches the dollar signs start increasing rapidly. To race a historic 956 or 962, for example, one reputable Porsche shop quoted me on the order of $5,000 – $6,000 an hour once you factor in crew, tires, brakes, race fuel and rebuilds. That, of course, doesn’t include the purchase price of the car which can easily exceed a million dollars – even for a non-winning chassis. Okay, so not everyone races Group C cars, but even 911s, 912s and 914-6s can be expensive to run competitively – and are increasingly expensive to purchase. One way to step a bit outside of the normal Porsche mold, then, is to look for the many privateer special race cars that were built in the 1960s, such as this DKW/Porsche hybrid “TM Special”: