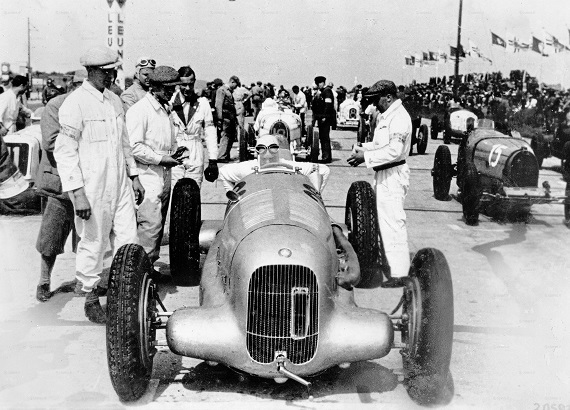

A 1934 Mercedes-Benz W25 lines up to race in front of a several Bugattis looking decidedly more aerodynamic and modern.

It seems fitting that a day after the Formula 1 season commenced in Australia with a resounding sweep of the top spots by the Mercedes-Benz W06s of Lewis Hamilton and Nico Rosberg. It was not particularly a surprise given the Mercedes-Benz domination of last year’s competition, yet it was a poignant reminder in light of the major difficulties faced by other successful racing manufacturers over the past few years with the new F1 regulations. While storied teams like McLaren, Ferrari and Red Bull have struggled to even finish at times, Mercedes-Benz has looked virtually unchallenged with wins only really contested between the two teammates. The same could be said of the original Silver Arrows between 1935 and 1939; however, in 1934 it was quite a different story when success was anything but a given:

TWO : NATIONAL SOCIALISM AND THE REVOLUTION OF AUTOMOBILE RACING

It was at the Berlin Automobile and Motorcycle Show in 1933 that Hitler, shortly after his appointment, first introduced his plan to revitalize the automobile industry. The plan called for removing state interests in transport, lowering taxes on automobiles, undertaking a giant motorway building process, and developing motor sports. Together, these factors were intended to spur the automobile industry out of its record slump following the American stock market crash, and to motorize the nation. All of these points had been pursued to some greater or lesser degree before the NSDAP came to power, but the combination and concerted effort was unique to the regime, intent upon modernizing Germany quickly through mass mobility. Though Germany has since gained the reputation of a nation of drivers, when Hitler came to power it was far from it. In 1933, Germany boasted 8 cars per 1,000 inhabitants, while France and Great Britain had 31 and 25 respectively. Because of massive currency devaluation, workers lacked purchasing power. The average worker in 1933 earned 21.88 RM a week, compared with 31.19 RM in 1929.

Despite his questionable long term intentions, Hitler’s plan to lower taxes to allow the motorization of the nation was clearly not a misguided need. Germany was woefully behind her stronger neighbors in terms of not only motorization, but also of its ability to purchase and use cars. Motorization was also key to Hitler’s plan for Germany to rearm, if only to have the ability to rapidly transport troops and equipment. Boosting the industry would provide the vehicles to support Germany’s rapid modernization and motorization of the armed forces, when they reached combat strength. Aside from that, Hilter apparently took notable interest in the development of the automobile. Hans Mommsen noted this in his study of the Volkswagen project, where he noted Hitler’s particular enthusiasm for sports cars and race cars as technological showcases. He took pride in his technical understanding of cars, and notably utilized Mercedes-Benz cabriolets as prestige symbols. Integral in his plan to motorize the nation was the development of motor sports. There were several reasons for this; the great victories of Mercedes-Benz in international races had reportedly coincided with a surge in exports and a general boost to the industry by raising the international reputation of the company and the industry. Further, the victories had bolstered nationalism on the part of Germans, who were glad to see a team from their homeland be victorious in a foreign land under the most difficult circumstances, against the best European opposition. Hitler’s championing of the effort to increase motor sports participation by the German car industry sounded much like the Autoclub of Germany (AvD) and the General Autoclub of Germany (ADAC) calls for a national subscription for the construction of a race car, and before them the Weimar government transport minister’s attempt to secure funds for Daimler-Benz, in order to create a surge in the industry.

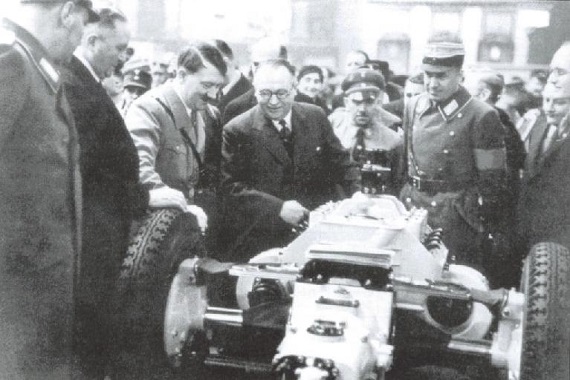

Hitler inspects the advanced alloy Tatra T77 internals at the 1934 Berlin Internationale Automobil-Ausstellung. The Tatra would be an inspiration along with Porsche’s rear engined designs for the forthcoming “People’s Car”.

The call for a national race car collection to fund the construction read all too much like the collection that had been taken up in the then not distant past – the Zeppelin collection. Following the third successive crash of one of his airships in 1908, Graf Zeppelin was about to concede defeat. However, the public had carefully followed and embraced Zeppelin’s progress in developing an airship and challenging the elements, and the hopes and dreams of the German nation had rested on his shoulders. Momentarily, Zeppelin – and with them, the Germans – had conquered the elements, and it stood gasping in awe at the size and modernity of her new airships. Certainly, the public would not let go of this advantage easily, and soon the cries went out to help Graf Zeppelin construct a new, stronger airship. In little over a month and in an unprecedented effort, the German nation had united in the cause of taking flight; the resulting nationalism equated to not only 5 million RM for the new Zeppelin, but also welling up of togetherness of the German people. The Zeppelin collection effort was repeated in 1924-1926, though the circumstances for the second collection were different: the 1924 collection was a call to Germans to unite once again in a singular cause, to show the world that Germany had not been completely defeated by the loss of World War I and the Treaty of Versailles. While not as successful in monetary numbers as the first collection, the second was equally good in spurring German pride and to once again instill Germany with the feeling that modernity and technology would raise her above her rivals.

In 1932, Germany once again lay in crises. Economic downturns combined with devaluation of the currency to cripple the automobile industry, among others. Establishing 1928 as 100%, Hans-Erich Volkmann established that production had fallen consecutively every year; in 1929 production was at 94%, 1930 62.4%, 1931 43.9%, and by 1932 production was 26% of the 1928 high . Companies such as Daimler-Benz lay helpless as they had rapidly watched their profits and turnover fall, resulting in massive cutbacks. Neil Gregor found that while companies such as Daimler-Benz had attempted to streamline and increase efficiency of their production processes to compete with foreign competition in the mid 1920’s, ultimately the company had to resort to a massive restructuring of the workforce by cutting skilled workers and eliminating redundant positions as the efficiency had subsequently resulted in over capacity . Construction of a race car itself, never mind supporting and developing the necessary team, was simply out of the question. The efforts of small automobile groups such as the AvD and ADAC would attempt to repeat the success of the Zeppelin collections in hope of achieving again what Mercedes-Benz claimed it had achieved in 1914 and in an even earlier victory in France in 1908: a victory which they saw spurring the entire industry through national pride. Yet in 1932 survival was all the industry could think about as production and sales tumbled further and further. In its 1932 company report, Daimler-Benz referred to 1932 as the highest point of crisis for the company – indeed, struggling for existence. Meanwhile, the Auto Union referred to 1932 as the crises year where the entire Reich’s production had fallen to less than a third of its 1928 highpoint of 1 million RM. By mid year 1933, the two automobile clubs had collected approximately 200,000 RM, which was earmarked for Daimler-Benz. In addition to this amount, Daimler-Benz had also supposedly secured funding promised by the Reich: an amount of approximately 450,000 RM plus monetary prizes for highly placed finishes in races. However, throughout its correspondence, the number 500,000 RM was tossed about; indeed, in a letter to Hitler from Daimler-Benz’s head of the Board of Directors Wilhelm Kissel in May 1933, Kissel extended the following greeting:

“We offer to you esteemed Mr. Chancellor, our expressed thanks for the allocation of aid. We are committed to ensure that the new race car type is completed as soon as possible, and that when it races it represents the reputation of the German automotive industry and our tradition…”

He referred earlier in the letter that it had been confirmed that assistance in the amount of 500,000 RM was to be dispensed to Daimler-Benz.

However, the fairly large sum of 500,000 RM was an enticement for other firms, as well, and the new conglomerate of DKW, Wanderer, Horch and Audi, named the Auto-Union, were eager to advertise their company as well, and racing was judged to be a perfect promotion for the company. The four Saxony-based companies had developed for the most part independently; Audi had been formed by August Horch, founder of August Horch Motorwagenwerke AG (Horch), after a dispute in the management of the latter company, and both built expensive luxury automobiles. DKW existed primarily as a motorcycle company, though it was also known for innovative designs; the name DKW originated from the company’s first steam powered vehicles, DKW standing for the German word Dampfkraftwagen, meaning steam-driven vehicle. Wanderer was another small but innovative company, producing medium sized cars and motorcycles. Formed out of the same need to survive the crises threatening so many companies in 1932, the Auto Union looked now to spread its name and increase sales. Having the German government pay for most of what it would cost to produce the car not only sweetened the deal, but made it possible. So noted Cameron Earl in his investigation into the racing of the period, when he noted members of the Board of Directors

“stressed the potential publicity value of the car to the organization, also drawing attention to the 500,000 RM per annum then being offered to firms producing sucessful Grand Prix machines. It was thought at the time this amount would practically cover the outlay of the production and maintenance of the racing firm.”

Daimler-Benz and Auto Union were aware of each other’s intentions, as also noted by Earl. He indicated that while Daimler-Benz was primarily pursuing construction of the race car to bolster the prestige of their firm, the company was “…no doubt influenced in their decision by the knowledge that the then newly formed combine of Auto-Union were at that time aquiring a new rear-engine racing car designed by [the notable car designer] Dr. Porsche, primarily as a publicity measure†. More telling, however, is the actual decision by the Auto Union Board of Directors to engage in race car construction. This occurred shortly after the Berlin Automobile Show, in March 1933, when a meeting of the Board of Directors discussed the development of a new type race car with Dr. Porsche, where it was stressed that a top-tier race program would act as propaganda for the entire model range. This was crucial for the company accepting racing as part of its budget. Also notable was that the company often conducted votes on racing activity with the export and propaganda departments directly involved.

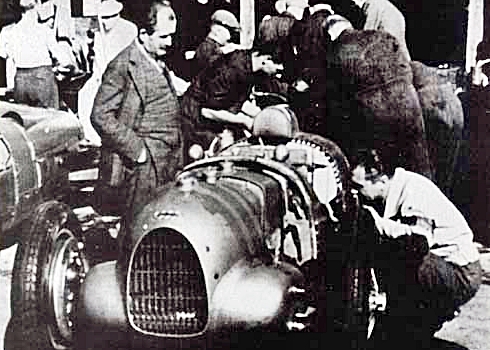

Dr. Porsche looks over the Auto Union Type B from 1935.

Both companies had reason to fear one another, as well as reason to promote themselves. Though the four companies of the Auto Union had all been smaller and more individualized when separate, together they formed a direct competition to Daimler-Benz. Indeed, fear of the Auto Union and other companies must have been paramount to Daimler-Benz’s decision to take up racing. Whereas Auto Union held 20.1 % of the new automobile registration marketshare in 1933, Daimler-Benz held only 9.6 %. In 1934, while Auto-Union’s portion had grown to 21.9% with the upturn in the automobile market, Daimler-Benz had actually fallen to 6.8 % . Auto Union achieved this primarily through diversity in range; while Horch covered the luxury car market and Audi covered the mid-sized/sporting car market, DKW was the real threat to Daimler-Benz with its small cars. DKW produced extremely small displacement cars (600cc and 700cc engine capacity versus the 1700cc smallest Mercedes) in order to avoid taxes levied upon larger engine displacement. Though these taxes had been eliminated by the new government, DKW’s cars remained inexpensive to buy and run, when contrasted with Daimler-Benz cars. This was essential to selling cars in 1933 and 1934, as although the government was promising future benefits of its programs, the reality was that few workers in those years processed enough money to purchase anything more than a small car, or indeed motorcycle. Opel had been first to break into this small car segment; being owned by General Motors of America after 1929, Opel had introduced mass-production techniques through assembly lines to Germany due to its American connection’s experience, and in doing so had successfully cornered the market for the small car through cheapness in production and standardization. Daimler-Benz, along with most of the rest of German manufacturers, found the small car market difficult to penetrate though it remained the largest segment of the market. Consequently, Opel was the largest automobile producer and seller in Germany, with 34.7% (unit value) of the market in 1933, and a staggering 40.7% in 1934 as the industry rebounded from economic crisis. The management at both Auto Union and Daimler-Benz thought efforts to generate a successful racing program were needed by the companies in order to secure a more substantial market segment. Market developments in 1933 and 1934 undoubtedly spurred both companies into action and justified their decisions to race; in Daimler-Benz’s case, the sinking market percentage called for radical action to promote the company’s automobiles, while Auto Union’s incredible growth because of its diverse range called for similar action to capitalize on the enthusiasm which had been shown for its products in the same time period.

The concern about each other’s activities can be clearly seen in the internal documents of the respective companies. For example, when considering the Führer’s proposal of constructing a race car, the Auto Union board of directors was careful to note that danger lay ahead if Daimler-Benz alone accepted this contract:

“The words of the Chancellor at the opening of the Motor Show strongly emphasized the sport friendly attitude of the government and has raised the risk that Daimler-Benz, if it is the only German company to build race cars of the top class, will become the national automobile factory in Germany. Thus, in order to counter the impending threat Auto Union has signed an agreement for the acquisition and construction of the finished construction of a 16- cylinder racing car with Dr. Porsche.”

At the same time, Daimler-Benz was well aware of plans by Auto Union to usurp its potential monopoly on the Reich’s offer of assistance, and was duly launching requests proclaiming Daimler-Benz as the logical company to receive the money, as their record of tradition in motor sports spoke for itself:

“The aspirations and the behavior of the Auto Union are not unknown to us. Therefore, we feel compelled to ask you to kindly take steps to ensure that the outcome of the collection is paid to our company. We base our request further as follows: We are the oldest car factory in the world, we have participated throughout our history in sporting events, to an extent, more than any other company, but also with unmatched success – whether this was the case before the war, or after the war”

As development work began on the Grand Prix cars at both companies, the removal of taxes on automobiles and the proclamations of Hitler began to take their effect on the industry, which had already began a modest recovery. From 1932 to 1934, new automobile registration of the top four companies in Germany – in both units and in market percentage of units – was as follows (Refer to Tabel 1):

Table 1 – New Automobile Registration in Units by Company(Percent of Total Registrations)

1932 1933 1934 (jan-jun)

Opel 12,436 (30.2%) 28,494 (34.7%) 23,849 (39.6%)

Auto Union 6,755 (16.5%) 16,465 (20.1%) 13,063 (21.7%)

Daimler-Benz 5,325 (12.9%) 7,844 (9.6%) 4,643 (7.7%)

Adler 4,735 (11.5%) 7,476 (9.1%) 3,621 (6.0%)

Source: Saxony State Archives, Bestand Auto Union 31050, Nr. 911, Zulassungen von Automobilen, p. 6 (chart) (apologies that this chart does not transfer well to this page)

In the end, it was a case of simple math. Auto Union, keen to spread its still new name throughout Germany and the rest of the world, saw racing as an opportunity to advertise its products to the world through the Grand Prix car. It may have also seen racing as a possible advantage for it over rival Opel, who did not participate in racing. With Opel holding a huge percentage of the market, and especially the small car market, the Auto Union was looking for a way to increase its portion. If the company could successfully compete on the same level as other notable companies – Alfa-Romeo of Italy, Bugatti of France and Daimler-Benz, all with long and illustrious histories in both automobile production and sporting history, it would certainly represent a marketing advantage over its rival. Opel, being already well known for producing small cars, had no such impetus to spread its name through international racing. At the same time, Daimler-Benz, whose tradition lay steeped in exactly that type of racing, watched its market percentage slipping away as the public scrambled to buy the cars that it could – the less expensive DKW and Opel models. Faced with an uncertain future and despite rising sales, a still rapidly shrinking market percentage, seemingly the company had no choice but to take the challenge to the Auto Union. This would be an exceptionally difficult challenge, as with higher end products, it would be exceedingly difficult for Daimler-Benz to meet the increases already shown by the Auto Union.

While Daimler-Benz was first to introduce its new race car design to Hitler early in the February of 1934, it was the Auto-Union race car design which captured the public imagination. When the news of the two German teams entering the French Grand Prix in 1934 broke, The Motor’s ‘Grande Vitesse’ noted that “[the] rear-engined super-streamlined and altogether ultra-modern P-wagens [Auto Union Type A race car] have tremendous pace…†. It was exactly the type of press coverage that the Auto-Union needed to legitimize its decision to enter racing. The article was, however, also the exact press coverage that the government wanted; in it ‘Grande Vitesse’ proclaimed that the public “shall see a battle royal between the Germans and the Italians on French soil, the Germans eager to show, the first time outside their own country, that when they do get down to designing a racing car it is an unbeatable proposition…†. The author was incorrect in asserting that it was the first showing of German Grand Prix technology outside Germany (Mercedes-Benz had convincingly won the 1908 and 1914 French Grand Prix), however, it was nonetheless perfect justification for the money offered by Hitler to the two companies – before the cars had even competed in a race! What the French Grand Prix in 1934 represented was, however, the emergence of the “new†Germany, and the fruits of the relationship between the ideology and economics.

Grid for the 1934 French Grand Prix – modern Mercedes-Benz W25 and two Auto Union Type As flank a more traditional Alfa Romeo Typo B/P3. Both proved too unreliable to win, but the Mercedes-Benz W25 shattered the track record by an astounding 14 seconds proving that the speed of the Germans was there.

This development, however, could not have come as a surprise to the government. The two firms’ racing plans had been carefully crafted by the government. Karl Ludvigsen noted

“[the] Reich’s financial participation had made it a partner in such deliberations. On 19 April in Berlin, Alfred Neubauer [Mercedes-Benz racing team manager] joined a representative of Auto-Union to meet with the regime’s head of motorization to discuss their 1934 race entries. ”

However, this meeting was not the end of the Reich’s involvement in the two teams’ forays. Ludvigsen continued: “supervision of the German Grand Prix effort was maintained by the Third Reich, which had set up an organization for motoring…this was the N.S.K.K. or National Socialist Motoring Corps, headed by a Hitler crony from the early days of the Nazi Party in Munich†. That ‘crony’, Major Adolf Hühnlein, was promoted to Obergruppenführer and later Korpsführer of the NSKK (national driving corps), but according to Dr. Ferry Porsche – Ferdinand’s son and heavily involved in the Auto Union project, “[Hühnlein] seemed to have absolutely no qualification for his job apart from a genuine interest in racing†. Hühnlein closely monitored all the races and record attempts, and reported back directly to Hitler. The Reich clearly wanted to insure its investment and secure its return, as they planned on exactly what the Autoclub of Germany had proclaimed was the result of the last major German Grand Prix effort: intense nationalism, growing international reputation for Germany, and increases in sales and scope for the automobile industry, all essential to the plan of national motorization and economic rearmament.

On the surface, National Socialism and Grand Prix racing made strange bedfellows. Yet both had to gain from the relationship; this was akin to many other special projects that started in aviation and military technology around the same time of Nazi rise to power. The government provided the necessary backing, with the inventors, designers and builders of such projects exploiting governmental intervention in order to best complete their projects. In certain cases, the ultimate results of the project mattered little; merely completing their project was the goal of the engineers. Michael Neufeld argued this was an all too common trait of the period, as he showed through the statement of Werner von Braun, the already notorious rocket pioneer;

“Our feelings towards the Army resembled those of early aviation pioneers, who, in most countries, tried to milk the military purse for their own ends and who felt little moral scuples as to the possible future of their brainchild.”.

Though by 1939 the synthesis of the Grand Prix car in Germany as a tool to build prestige for the company and an example of the supposed Nazi superiority was complete, in 1933 the race car designers at Daimler-Benz and Auto-Union had little reason to believe that their race cars would be used for anything other than racing. In the same regard, the Reich government had only aspirations of promoting the automobile industry, and hopes that its new venture would be successful based on only the Mercedes-Benz past experiences – claims of the inherent superiority of German designs would have to follow race wins, which was still only a dream at the time. However, both had little to lose – and indeed with money available, skilled engineers in both companies and a clean slate for the new race formula, both the government and the companies had everything to gain by any success. It is also important to remember when considering the enthusiasm of both companies regarding the government’s support of their race programs, that they – specifically Daimler-Benz – had been promised money on several occasions. Once again, they had been promised money, but this time it came through. Emerging from a massive crisis into blooming sales, it is easy to understand the lavish praise the companies placed upon the government and especially Hitler. Auto Union was not alone when in its company report it claimed that the government, and particularly Hitler, were responsible for the massive growth in their industry, claiming he had ” liberated the industry from the shackles of an inhibitory control policy”. Mercedes-Benz echoed the sentiments in their company report of 1933, where they praised the personal initiative of the Führer for a strong boost to the industry:

“The programmatic declarations of our Chancellor at the opening of the International Automobile and Motorcycle Exhibition in Berlin on February 11, 1933 showed the new way of purposeful motorization of Germany and the future importance of the automobile in the German economy . His Announcements gave our industry a major boost .”

Also, racing offered a venue to explore limits which had not previously been considered. While the airships of Zeppelin and gliding had forced the development of increasingly aerodynamic (and futuristic looking) designs which had captured the public’s imagination, those boundaries had generally not been pushed by the automobile industry. However, this trend began to change in the late 1920s and early 1930s. By the German Grand Prix in 1932, Manfred von Brauchitsch had a special body fitted to his Mercedes-Benz SSK. The streamlined body had notable advantages; its decreased wind resistance allowed him to win over a non-streamlined car by virtue of increased top speed . This win showed the clear advantages of streamlining to the race car designers; unsurprisingly, both German firms’ new cars were incredibly streamlined when compared to the competition. While this was intended to increase the efficiency of the design, the end result of the streamlining was that the cars looked the part, and everyone noted their incredibly advanced design. This “super-streamlined and ultra modern†design, when presented to the public by both teams, not only captured the attention of the people eager to see their undoubtedly incredible speed, but it also rendered all of the contemporary designs immediately antiquated.

Grid for the early 1935 Tunisian Grand Prix – the sole modern and unconventional Auto Union Type A (No.34) of Achille Varzi lines up against more traditional Alfa-Romeo, Maserati and Bugatti Grand Prix cars. Varzi would win by nearly four minutes, signalling the reign of the Silver Arrows had begun.

End Part Two

-Carter