1938 Coppa Acerbo – Mercedes-Benz W154s and Auto Union Type Ds leave the starting line

We’re going to run something a bit special over the coming few weeks; a bit of a history lesson. In light of the 2014 championship for Mercedes-Benz in Formula 1, I wanted to revisit some research I did in 2003-2004 as part of a Master’s program at the University of Cambridge. We take it for granted that large corporate sponsors and major automobile manufacturers engage in motorsports as a natural outlet and expression of their engineering prowess in order to help sell brand identity, brand loyalty and ultimately sell more cars, trucks and motorcycles. Yet, there was a period where this was not a certainty – indeed, in the early 1920s it was still presumed that racing was an endeavor only rich gentlemen partook in, much like horse racing. But the combination of two companies competing against each other, a government eager to tout the superiority of its products, and new technologies all combined in a very special period during the early 1930s. The reign of the Silver Arrows was only halted by the outbreak of war, yet during that period of roughly 6 years we saw some of the fastest, most powerful and most exotic designs be innovated by the two German marques that the world has ever witnessed. The Mercedes-Benz W125 would remain the most powerful Grand Prix car for 50 years, until the 1980s turbo era, and properly streamlined, they still hold closed-course records in Germany at 270 m.p.h. on the public Autobahn. The spectacle held not only Germans attention, but all of Europe looked on as these two Goliaths tried to outsmart and outspend each other. Ultimately, they went to extremes to prove their dominance and win the favor of the German people – but more importantly, the German government, who by the late 1930s increasingly held the purse strings to valuable commodities needed for the production of automobiles. The following tells the tale of how the two German marques became involved in Grand Prix racing, how successful each was, and problems and challenges they faced along the way. It’s told from more of an economic standpoint, to help to explain why the two firms would race Grand Prix cars when neither offered a sports car for sale to the public. For the purposes of this blog, I’ve removed the citations and many of the quotations (most of which are in original German) as this is already quite long. I hope you all enjoy it, and if you have any specific questions please leave comments and I’ll do my best to answer them! Without further ado…

It has been called by many the ‘Golden Era’ of motor racing, when there were no sponsors’ stickers covering the cars, no television coverage, and few safety devices that mask today’s drivers. The open-cockpit cars from the 1930s evoked romantic images of World War One aces, with leather helmets and sheer ability the only things keeping them from death. The cars achieved remarkable speeds, their drivers even more remarkable feats. The drivers who tamed the beasts from Auto Union and Mercedes-Benz came to be fabled even among their contemporaries, with mythical names like ‘The Rain Master’ and ‘The Mountain Master’, as they drove into motor racing history. Yet this period of extreme romanticism and incredible achievement existed under the shadow of one of the darkest periods in human history – the mythical ‘Silver Arrows’ of the two teams, while flying into the record books, also flew swastikas on their tails.

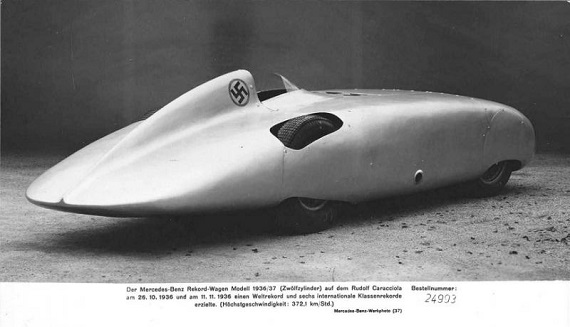

Mercedes-Benz W125 Streamliner V12 record car topped 231 m.p.h. in 1936. They would be even faster the following year

What was the interconnection between the Nazi Party and the Silver Arrows? Traditional scholarship has treated the two as separate topics. Those who have studied in depth the technology of the Nazi government and the economy have ignored the race cars as little more than promotional tools of their respective companies. Authors such as Richard Overy, Fritz Blaich and Heidrun Edelmann, among others, have studied the economy and the automobile industry under the Third Reich, yet generally only mention the racing phenomena in passing. Conversely, automotive historians in general have dealt only with the cars, characters and results, failing to delve into the relationship with the government, or indeed why the government and companies were interested in racing. Of all of the writing on the topic, noted automobile historians Karl Ludvigsen and Chris Nixon have done the most complete work to date, though both works have limitations. Ludvigsen concentrates almost exclusively on the Mercedes-Benz story; not a historical fault, but it omits half of the story. Conversely, Nixon’s work on the Silver Arrows paints the picture of the overall developments through the characters of the period. In telling the entire story, this source is invaluable, as it is the only one to consider the entire period and both teams. Where Nixon’s work fails, however, is in explaining the relationship between the Reich and the companies – and again, why both were interested in racing. Race results affected more than just score cards, yet the larger meaning of race victories is often lost in automotive histories. In general, automotive historians tend to take for granted that the existence of racing is sufficient justification for its undertaking; they often fail to consider what the impetus to race is for an automotive company. The truth is quite far from either of these scenarios. Rather, the Silver Arrows were a pivotal aspect of the National Socialist plan to motorize and modernize Germany; they were the international ambassadors of German technology and were an ever constant reminder of how far the regime was willing to go to win. The racing cars were not only instrumental in achieving the regime’s aim of increasing the international prestige of Germany among her neighbors, but they were also key in promoting her automobile industry, which was in desperate need of assistance in 1933.

Primarily this essay focuses on how National Socialism and racing cars came to be interested in one another, and indeed why the Auto Union and Mercedes-Benz became interested in participating in racing. To better explain the multiple aspects of the period, the essay has been broken down into five sections. The first section will describe the origins of motor racing in Europe, focusing primarily on the rule changes which led to the new racing formula in 1934 under which the Germans raced, as well as outlining what the benefits and motivations were for those participating in motor racing. Section two expands upon those ideas, encompassing them within the context of racing under National Socialism in Germany. It attempts to explain why the NSDAP, and specifically Hitler, became interested in racing, as well as why the companies Daimler-Benz and Auto-Union became the two willing participants. The third section focuses on how the two German teams and the Reich’s government redefined automobile racing, both through their participation and their inter-connections of the government and companies. The fourth section details with increasing government influence on racing, and projects that were possibly outside the companies’ initial interest in racing. Finally, in section five the advantages and disadvantages to not only the companies, but to the government and country are discussed. The hope is that through this essay, some light will be shed upon the interdependence of the government and the two companies upon one another, while examining the results of this extremely complex relationship.

ONE: THE ORIGINS OF INTERNATIONAL GRAND PRIX RACING IN EUROPE

By the early 1920’s, European automobile racing had eclipsed its earlier form of a gentleman’s sport and achieved a new form – sanctioned by an international body (AIACR – Association Internationales des Automobile Clubs Reconnus), in which races of set lengths were held which combined endurance and speed. Though the term “Grand Prix†had come into existence far earlier in France, it was in the 1920s and 1930s that the term came to represent the pinnacle of automobile sport – where the best drivers, cars, companies and technology was to be found. The cars that drove in them would have few rules to comply to, although there were other limitations which inspired their designs. Leading up to the 1930’s, a series of rule changes was instituted by the AIACR which ultimately hurt competition. By imposing strict rules limiting engine capacity and weight, many major firms such as the French Delage and Italian Fiat pulled out of the racing. Combined with sharp downturns in the economies of Europe following the U.S. stock market crash, nearly all major company efforts had been eliminated, leaving only private drivers to enter their own cars, at times with factory help. In an attempt to bolster the competition, the AIACR removed all restrictions on racing in 1931, allowing any engine size and vehicle weight – with only stipulations for race distances .

What followed was a huge leap in speed, as cars with giant engine capacity – and resulting horsepower and speed – came to dominate the race circuits of Europe. Concerned about this turn in speed, the AIACR established a new set of rules which remained in effect from 1934 to 1936. Though race distance remained the same (500 km), the vehicle would need to weigh less than 750 kg before the start of the race. This rule was made based on existing knowledge of race car design, which was primarily influenced by production sports car design, whereby the car competing in the event was mainly based on a series production car. To this point, while there had been team organizations, for the most part individuals had raced the cars with some degree of factory support. For example, though Daimler-Benz (through Mercedes-Benz) was not racing as a company, the company was sure to put their best cars in the hands of individuals who could win the races – Rudolf Caracciola, Hans Stuck and Manfred von Brauchitsch being the perfect examples, with their factory-backed ‘SSKL’s in 1931. While the SSKL was based primarily on a Mercedes-Benz sports car, it had been heavily modified and lightened so that it was very fast and, consequently, successful . Despite the assistance provided by the company, however, the SSKLs were not a full factory effort; it was still up to the individual to provide most of the funding to participate in races. Thus, the idea that racing was a ‘rich man’s’ or gentleman sport continued; there was virtually no way of entry into the sport without money.

Cars such as the SSKL were the reason the AIACR decided on its rule change . By limiting the weight of the car, it believed that they would necessarily limit engine size and speed. What they didn’t anticipate was progress: progress in engine design, lightweight materials, and full factory efforts. In 1933, motor racing stood unknowingly at the beginning of a revolution despite the severe economic crisis which had forced companies such as Daimler-Benz to curtail even their limited racing.

Why would these companies be involved in such a sport, however? At the beginning of the century, racing had been established as the benchmark for performance, reliability, quality in construction, and technical ability of the company producing the race car. In addition, racing was a spectator sport involving thousands of people coming to spend their money to see the race cars compete and enjoy the pure spectacle. Slowly, racing segmented into specialized groups. Sports car races, such as Le Mans in France and the Mille Miglia in Italy offered a chance to test the reliability of a car, as they subjected the entrants to a grueling endurance race. Grand Prix races, on the other hand, were usually a shorter race involving a smaller circuit which therefore allowed more radical designs (as they did not have to be subjected to long term reliability tests) and hence more speed. The cars that grew out of these two forms began to differ from their respective companies’ series production cars. This occurred in varying degrees; as previously mentioned, the SSKL of Mercedes-Benz was a heavily modified sports car, while cars such as the French Bugatti “Grand Prix†Type 51 and Type 35 sat on their own specially designed chassis to best win the sprint races.

Firms such as Mercedes-Benz, Bugatti, Alfa-Romeo and Bentley all managed to show the direct and indirect advantages of automobile racing. In the case of both Bentley and Alfa-Romeo, their sports cars were modified to race in international competition in the later 1920s with great results; directly showing to potential customers that their sports cars were serious performance cars. On the other hand, international Grand Prix racing had an indirect effect on the company, for while the car being raced might not be a production automobile, the successful racing of a car by a marque would lead people to believe that the company produced quality automobiles. Bugatti was the perfect example of this; while the company produced successful Grand Prix cars, it was well known to customers for extravagant luxury automobiles.

This phenomenon was shown by Michael Noetzel when he examined the results of the 1914 French Grand Prix. In that race, the Mercedes-Benz team had entered five cars and claimed an overwhelming victory over the competition after a strong showing of team tactics. Noetzel concluded that being able to claim victory in competition and demonstrating the inner strength of the company held more value to some buyers than technical considerations alone. Though the company may not have won on technical merits and rather simply by number of entrants or company organization, the win could still have a large effect on the consumer. The ability of the company to produce winning race cars, and indeed its commitment to success in racing, spoke for the ability of the company. Later on, Auto Union also touted this connection in their propaganda regarding their racing. In a pamphlet entitled “Triumph in the USAâ€, the company claimed that Bernd Rosemeyer’s victory at the 1937 Vanderbilt Cup race in New York

“proved once again in convincing style the marvelous efficiency and reliability of the Auto Union products. Universally acknowledged like the achievements of the victorious Auto Union racing cars is the unrivaled quality of the Audi, DKW, Horch and Wanderer cars…they carry the same badge, four rings of the Auto Union, as a sign that the same workers and engineers have been instrumental in their construction and subjected to the same rigorous tests.”

This was certainly an exaggeration for advertising purposes, as the engineers of the race cars were totally occupied with that singular task. Despite this omission, it was clear that the company wanted the public to see the link between the race cars and the production cars – as technically there were few at this point. The buyer of the Auto Union was not purchasing a car that itself was necessarily a winning design, but they were buying a product of a winning company.

In addition to advantages gained by the company participating in racing, there were also benefits to the entire industry, to the region in which the race was taking place, and to the country as a whole. The entire industry was assisted as a result of the advantage to the country as a whole; as the public saw a British, French or German car winning a series of races, they would perceive that cars originating from that country were better. How could the public so easily distinguish between products of differing countries? Strategically, cars before the 1930’s were color-coded by nationality: German race cars were white, British were green, French were blue and Italians were red. In addition to simplifying the identification process, this system undeniably added to the nationalistic aspect of racing. In a letter of appeal by the Autoclub of Germany in 1932 to build a German race car, they said racing brought money and prestige along with the cars that raced; this was an advantage not only to competitors but also to the area in which the race took place.

Direct and indirect advertising for the company aside, motor racing provided something much more to the industry and the country. With motor racing victories, companies gained prestige, but also drew crowds who spent money to watch them, and benefited the area. The companies hoped that when considering a new car purchase, motor enthusiasts would naturally migrate towards the marque with a victorious race heritage. However, in the international arena motor racing attained new heights, as one began to factor in exports and imports in addition to international prestige. The Grand Prix, representing the highest form of the sport in terms of performance, became the unwitting ambassador of international relations. In 1934 Rodney Walkerly, under the penname ‘Grande Vitesse’ and writing for the weekly British car magazine The Motor, commented in an article entitled ‘What is the use of Grand Prix Racing?’,

“[how] many thousand times more worth while is it to win an international race, a race in which not only are makes pitted against each other, but…each nation considers itself pitted against national in the symbolism of their great Grand Prix cars…”

Thus, not only were German cars beating French cars and Italian cars in the Grand Prix of 1914, where they had so convincingly won, but now the Germans were beating the French and Italians, in France. The resulting swell in nationalism only a taste of what was to come.

Indeed, Dr. Bruhn of the Board of Directors of the Auto Union company later claimed that there were three main areas of benefits for Grand Prix racing – political, economic and technical areas. Bruhn outlined all three of these areas in explaining why the Auto Union would come to participate in the Grand Prix racing. In a later speech Bruhn described the effects of racing in his article entitled “Ist der Kraftfahrsport wirtschaftlich vertretbar?â€. This article detailed the various effects of motor racing, including effects of economic, political and technical advances. Daimler-Benz was well aware of the benefits of racing, as well. In a 1927 company report regarding exports, it noted that “Without propoganda we cannot survive abroad†. Racing cars provided exactly that propaganda that they needed; a perfect rolling advertisement of the company’s ability and achievement. This was assisted by the fact that Mercedes-Benz was the only German automobile producer that had been involved in successful racing on the Grand Prix level before 1934. Dr. Wilheim Kissel would note this in a letter to the Autoclub of Germany. Despite the many benefits of automobile racing, the post 1928 depression had left much of Europe in such a state that automobile racing on a large scale was quite out of the question. Asked by the Reich Traffic Minister following Mercedes-Benz victories in 1931 which assisted the areas in which the races were held if Daimler-Benz could once again produce a car to win races, Dr. Nibel of the company had to reply in the negative – the company simply did not have the funds to support developing a new race car.

The result was that privateers once again came to the forefront, though in order to win they chose the best available cars instead of relying on what the companies in their country could produce. Thereby, Rudolf Caracciola, the German who had successfully won the German Grand Prix in 1931 driving a Mercedes, found himself in 1932 driving an Italian Alfa-Romeo . All of the previous success was brushed aside as Germany’s major competitors in automobile racing, France and Italy, contested the German Grand Prix without a German car able to match them. The situation was unthinkable to the Autoclub of Germany, who lamented that the country where the automobile had been conceived, despite a wealth of capable drivers and technicians, was unable to produce a car capable of winning major international races as it had so successfully before. Within twenty years, Grand Prix had gone from its height of popularity in Germany to non-existence through the war, back in popularity through the 1920s and had once again fallen with the new economic crisis.

The situation did not go unnoticed either by the newly appointed Chancellor of Germany, Adolf Hitler, in January 1933. Prior to this, the Autoclub of Germany and another car club, the General Car Club of Germany (ADAC) had both undertaken efforts to start a national collection to gather money for what was considered the most capable firm, Daimler-Benz, to construct a new race car for Germany to compete under the new formula for international races established by the AIACR. At this point Daimler-Benz was ironing out details for funding this project, expected by those within the industry to cost around 1,000,000 RM. In coming to power, Hitler may have been made aware of promises from the previous government to Daimler-Benz of assistance for construction of a new race car by the company, but which had never come to fruition, as noted by Kissel. Hitler was, no doubt, also influenced by his close friend Jakob Werlin, who also happened to be a member of the Board of Directors of Daimler-Benz. Hitler chose to champion the cause and push the industry to involve itself in racing. According to several authors, Werlin had been re-employed by the Daimler-Benz company following the appointment of Hitler in order to exploit his personal relationship with the chancellor for the company . Hitler was likely further driven following his only attendance of a Grand Prix, the German Grand Prix at Avus outside of Berlin in 1933. Though German cars and drivers had been victorious in previous years, Chris Nixon noted “[on] this occasion, however, Hitler was faced with the humiliating sight of foreign cars and drivers filling the first three places†. Spearheading the effort meant that whatever the outcome, the next German race car would be linked to the government. However, with his close links to the motor industry and goals of German motorization, this was anything but coincident.

Pierre Veyron and his Bugatti Type 51A GP won the 1933 Avus Race. Also pictured is Ernst Burgaller who came second, also in a T51A Bugatti.

End Part One

-Carter

Great topic. Anxiously awaiting part two.

Fantastic research Carter, thanks for sharing it with us!

Thanks guys, tune in next week for Part 2!

Thanks Carter for sharing the results of your research and enthusiasm. Amazing stuff. Taking GCFSB to another plane!

Thank you Doug! Glad you enjoyed!

Comment from Stern (lost in transition of servers):

Comment: Interesting topic, and yes, curiously absent from most histories. As a MBUSA club member, I can tell you that any articles in The Star magazine about the Silver Arrows from this era definitely gloss over any connections to the third reich. Looking forward to part two!