A Mercedes-Benz W125 leads an Auto Union Type C – the height of power for these Grand Prix cars in 1937

As we’ve seen in the last two parts, both the motivation and need was present for a concerted racing effort by the Germans. The promise of political and economic support from the government only sweetened the deal for both Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union. What resulted, as we’ll see, redefined what it meant to go racing – not only for Germany, but for the world.

Link to Part 2

THREE : REDEFINING AUTOMOBILE RACING

In theory, the successful plan worked perfectly for all involved. The two car companies would gain international prestige for themselves while boosting domestic car sales through promotion of their abilities, while the government – their fairly public backer – gained support for the entire automobile industry, cash flow for the country through increases in sales and exports, and international prestige for Germany as a whole as well as promoting the modernity and advanced state of German technology. In practice, however, there was a drawback to the plan for the two companies. The problem derived from the rules and competing against one another for the same prize.

The rules presented a problem because in an attempt to quell every increasing speeds, the AIACR had established the 750kg maximum weight rule based on 1932 technology, believing that in order to go fast the car must be larger and heavier. This had certainly been the case in the past, whereby under free racing regulations constructors had merely installed two racing engines into the car and combined their efforts – with resulting staggering speed. However, under the new racing rules both Daimler-Benz and Auto-Union developed cars that met the requirements, yet provided even more powerful engines. The result was incredible speed, speed that had never been seen before at this level. Cecil Kimber, a prominent British motor mogul, commented in 1936 that the new generation of Grand Prix cars were “amazing pieces of mechanism in which engines of up to 5 litres were employed in cars weighing about the same as an English sports car of nominal 8 h.p., but capable of a speed of 200 m.p.h. on an ordinary road!†The technical difficulties of such an endeavor were well known to designers and racers alike; noted one racing historian of the development of the first on the Mercedes-Benz Silver Arrows, “The designers were taking a grave risk with a 4-litre engine developing 400 h.p…however, (Daimler-Benz) had decided to build something fully thirty miles an hour faster than anything produced yet…â€. Speed, it must be remembered, is not a linear function, but rather increases in relation to the force required to overcome drag; hence, increasing speed from 100 to 150 m.p.h. takes less power than a corresponding increase from 150 to 200 m.p.h.. A thirty m.p.h. jump over the existing standard required more power, a better chassis, more streamlining, better brakes and tires, and more money.

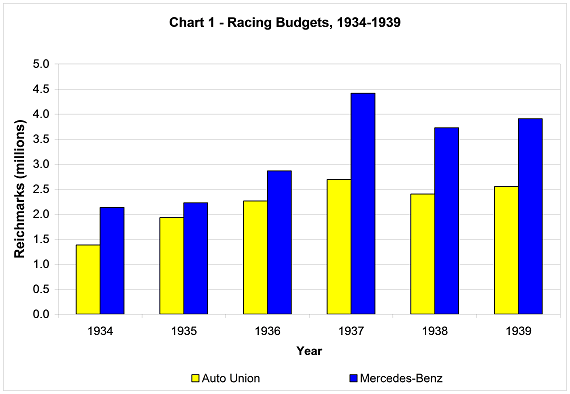

Once the problems plaguing reliability had been worked out mid 1934, Daimler-Benz and Auto-Union realistically only had one competitor – each other. The result was that racing budgets skyrocketed as new technology pushed the envelope of what was considered to be a race car. Quite simply, this period of competition, under the free formula from 1934 to 1937, revolutionized automobile racing. Whereas in 1932 Kissel from Daimler-Benz had suggested 1,000,000 RM would fund a racing team, by early 1935 Daimler-Benz was spending 250 % of that figure – the race budget for that year was 2,448,647.43 RM. Auto Union could not escape a similar fate; though as we have seen, the company hoped that Hitler’s 500,000 RM subsidy would cover most of the expenses of racing, they had spent 300% more -1,901,191.66 RM – to race in 1935. Yet despite this shocking operation over-budget, the gap only became worse as the competition between the two companies grew ever more serious. After an unsuccessful season in 1936, Daimler-Benz simply out-spent its rival in order to race, and reached a new peak in doing so, spending 4,415,150.00 RM in 1937 (equivalent to around $28,500,000 today) to convincingly beat the Auto Union team, which had invested only around half of that amount. The plan worked; Mercedes claimed more victories than Auto-Union in 1937.

The AIACR changed the rules for 1938 with limited engine size and increased the weight of the cars in a hope of slowing down the two teams, it did little to reduce the budgets. During this period Daimler-Benz showed its clear advantage to the Auto-Union in team management and organization; the company had incredible resources devoted to designing, testing, developing and racing cars. While the ‘Silver Arrows’, as the two teams’ cars were together called, redefined what racing involved, they had other unintended consequences. Certainly, the radical designs employed, as seen with the Auto-Union, had gained public attention. Without a doubt, the 1937 Mercedes-Benz W125B – the last of the great free formula cars, had simply overwhelmed the competition with its 650 horsepower engine – no less than three times the horsepower of the “fast†cars the AIACR had feared so much when it instigated the rules to limit speeds. More fundamentally, though, the Silver Arrows signaled fresh representation of Germany internationally; while the national racing color of Germany was officially still white, the cars from Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union were now silver. A minor point, yet nonetheless an indication to the public that times had changed.

Manfred von Brauchitsch catches air at the 1937 Donington Grand Prix in a Mercedes-Benz W125B

There were even more fundamental problems besides budgets, initially felt by Auto Union. As stipulated by the original contract with Dr. Porsche, the Auto Union – constructed race car was named the “P-wagenâ€, standing for ‘Porsche car’. As the car began to gain publicity soon after its introduction to the press, it was not the Auto Union gaining the publicity, but rather Porsche, as his name was inscribed in the car. For the company that had entered into racing for the sake of publicity, this development was troubling and caused great concern. Von Oertzen, one of the leaders of the Auto Union racing program, described this concern in a letter to Porsche in early 1934 – stating that the car needed to be known by the public under the marque Auto Union rather than Porsche. While a nomenclature discrepancy may seem a trivial matter, it was anything but to the company. In order to link race participation with sales, the company had to have the public readily associate its records and victories with the company’s product line. Realistically, the only way to identify the Auto Union race car and production car were the four rings and the name. Porsche allowed the name change; a pivotal decision in the fate of the company, as the original contract, as Porsche pointed out in his response to the company, stipulated the race car to be named after its designer . With these matters cleared up, the Auto Union was free to pursue racing – and to link that racing with its series production.

Dr. Porsche and Hans Stuck standing over an Auto Union in early 1935

The series of success generated intense interest within Germany. The results harkened back to the reaction of the public to the new Zeppelin airships of the turn of the century. Peter Frizsche noted that the first Zeppelin inspired celebrations of

“not only the imposing technical accomplishments of the Zeppelin but also the construction of a heart-felt and popular nationalism…, the great duraluminum dirigibles displayed the technical virtuosity and material achievements of the German people… [At] the same time, the…Zeppelin was an affirmation of German prowess and overseas expansion.”

The Silver Arrows were steeped in modernity, just as the Zeppelins had been, and now represented the hopes and dreams of the Germans. While Fritzsche claimed that 250,000 Germans came to watch the Zeppelin glide silently overhead, now 400,000 Germans traveled to the Eifel, to the Nürburgring, to watch their race cars scream through the mountains. Just as the Zeppelin phenomenon had captured the attention of the international press, the English press now looked in awe –

“Next Sunday, July 25, the most important race of the year will be fought out on the 14 miles of twisting Nürburgring, a couple of thousand feet up in the pine-clad Eifel mountains near the Rhine. Last year over 400,000 Germans watched the race. This year the attendance is expected to break all records and reach the half million mark! It is probable that 500,000 people have never watched a sporting event of any sort in this country, and the sight of the vast crowds streaming to the circuit from all quarters for 24 hours before the race is one of the most staggering things that a British racing enthusiast could possibly imagine.”

Indeed, the British press seemed to view the race as only a minor part of a larger social trend in Germany. The event would begin nearly a week in advance of the race, as people started to make their way towards the track, and would last long after the cars had been parked by their drivers after the race. This was well described by ‘Grande Vitesse’ in his article ‘Motor Racing – German Fashion’. The mere title indicates that even in 1937, the motor world was well aware that the Germans had redefined what racing was. More importantly, they were also well aware that the government was a large part of this shift in racing, as its relationship to the companies – something of speculation in the press – was a newly introduced factor. The government, sensibly, aligned itself with the victories by celebrating their grandeur. Chris Nixon noted how the Grand Prix cars would be paraded in front of audiences down city streets in Berlin before the yearly automobile show, where soldiers would hold back the crowds in what was “a vast display of Nazi prowessâ€. Nixon further commented,

“[on] each occasion the streeets and buildings were decked out with Nazi flags and swastikas, making the whole affair into a political rally, but that aside, it was a brilliant example of public relations to let the workers share in their teams’ success.”

Much like the political rallies, Zeppelins flew over the crowds at the German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring. Such trends added to the socialism of the sport, as the victory became not the work of an individual, but the work of a community.

In some ways, the cars of Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union can be seen as having picked up the reins of the gliding movement from the 1920s. Peter Fritzsche argues that after the fragility of the Zeppelins and the reality of lack of powered flight stipulated by the Versailles Treaty set in, the public took to gliding as a mass public movement, in a sign of defiance of the chains that bound her to the ground. However, once the 1930s rolled around, powered flight had once again taken control of the skies in Germany, and as the national airline Lufthansa established more and more air routes, some of the mystique of flying was lost on the public. The Grand Prix cars stood poised to take over the public fascination; like a battle of fighter aces from World War One, these great pilots of the ground took to their new steeds to defy physics once again, albeit this time much closer to the ground. Pushing the limits of technology had been established by both the airships and the gliders; the race cars were the next evolution of this trend.

Beyond this, Mercedes-Benz and Auto-Union now represented the German nation abroad, and the resulting overwhelming conquering of her competitors instilled a measure of fear and awe into the competition. Motor enthusiasts were split between being awestruck and furious when the two German teams were invited to Britain’s Donington Park in 1937. Since the British had no car remotely capable of matching the Silver Arrows, the crowds were merely treated to a display of German racing prowess. Many, therefore, questioned the wisdom of allowing the German supremacy at Donington, as it had precluded a British car and driver winning the race. One prominent British designer commented, “…fools that we are, [we] invited these all-conquering German teams to come and compete at our Donington Road Racing Circuit…Naturally, these colossally expensive and extremely fast cars…made our own…look sillyâ€. Noted one correspondent after the race, “we should have played the German anthem, we should have stood up, and we should have given three cheers for the men who had entertained us so wonderfullyâ€. Noetzel noted that Kissel stressed the awe-inspiring aspect of the race cars in his essay entitled Vom Sinn der Autorennen when he stated that foreigners were aware of two intimidating German institutions – her warships, and her race cars. The race cars were undoubtedly successful in intimidating the neighbors of Germany, who could only watch at their ever increasing speed. While this was certainly beneficial for the larger aims of the government, it is doubtful that the companies’ aims were to generate jealousy and intimidation in the foreign press.

1937 Mercedes-Benz W125s and Auto Union Type Cs line up to race against outclassed competition with an attentive crowd looking on

At the same time, there were those that recognized within the industry that the connections to the government were not necessarily advantageous for the companies. This was well represented by Horst Mönnich in his history of BMW;

“People coming to BMW (even the Führer) were not bringing glory to BMW but only to themselves. [The head of BMW] knew what [Hitler] wanted – results. Successes in racing, records. Every race that was won added to German’s glory, made the Germans stronger, showed the world who was really the boss…New designs, recognizable by the high-pitched whining of their superchargers, appeared on the race-tracks of Europe, where they won victories, flew the flag…The Germans were coming! “

The government used its contributions to companies such as Auto-Union and Mercedes-Benz to link their victories to a larger idealism: the supremacy of the German technical industry. However, to substantiate the claim that Germany was superior to her rivals, the government needed a series of victories to establish continuity. Mercedes-Benz and Auto-Union, with their five years of Grand Prix racing, provided just that. For this reason, Hühnlein was able to claim in 1938 “We are particularly proud to point out that the German race cars and racing motorcycles in all parts of the world have won 90 Grand Prix and hold 17 world records and 40 international class records.”

More simply, the two teams dominated nearly every event they attended – and the cars had fulfilled the destiny proscribed to them by The Motor in creating an “unbeatable proposition†in Grand Prix racing.

Despite changes to the rules in 1938 and 1939 intended to slow the Silver Arrows down and increase competition, the two companies remained in an unassailable position until the outbreak of war. They continued to win races and hill climb events, all the while building to the mystique of their existence as well as the reputation of supremacy of German technology. It was Mercedes-Benz that became increasingly successful in the last three years of racing before the war, as again they simply outspent Auto Union to develop a superior car and superior team. Mercedes-Benz’s greater number of victories over the same period can be seen as a direct function of its increased spending over the same period of time. With more money to develop its cars, it was the years of extreme change in 1937 and 1938 where the money spent by Mercedes-Benz showed its benefits. The introduction of the new race formula in the 1938 season demanded an entirely new car to be designed alongside the existing – and already expensive – 1937 race car. Mercedes-Benz’s expenditure in these two years far outpaces the Auto Union, with the result that in both years Mercedes-Benz was notably more successful than its rival. The spike in spending in 1937 represents the additional work in development that the company expended on the development of the new model.

Mercedes-Benz and Auto-Union racing budgets, 1934-1939. Source: Auto Union figures : Saxony State Archive, Bestand Auto Union 31050, Nr. 790, Letter to Hühnlein from Auto Union 26 January 1937 (1934,1935,1936), Subventionen des RVM für Entwicklung, 7 September 1939 ( 1937,1938), Letter to Reich traffic minister, 16 December 1939 (1939). Mercedes-Benz figures : DaimlerChrysler Archives, Bericht über die gebuchten Kosten für den Bau, die Entwickelung und sportliche Verwendung des neuen Rennwagentyps, 1934, 1935, 1936, 1937, 1938, 1939

Kissel pointed out Mercedes-Benz’s achievement against the odds under the new rule change in a letter to Hühnlein, where he noted that common belief would have dictated that the new 3 liter formula would have resulted in fewer victories, but that the team’s success was even more overwhelming than before. Conversely, Auto Union lamented at its lack of development and adequate drivers in 1938, as both had been hampered by the death of star driver Bernd Rosemeyer early in the year. Rosemeyer was one of the few drivers that had been able to master the unusual handling dynamics of the Auto Union. Coupled with the change in formula to 3 liters, the company was not nearly as optimistic about the 1938 racing year as Mercedes-Benz.

The death of Rosemeyer was a blow to the company, the government and the country for another reason. While the cars and teams were reestablishing the standard of automobile racing, drivers like Rosemeyer and Hermann Lang from Daimler-Benz were redefining who could be involved in racing, and hence to some extent who racing appealed to. Unlike the established veterans of racing, Carraciola, Stuck and von Brauchitsch, Rosemeyer and Lang both came from modest backgrounds. While Rosemeyer attained his race seat through his exploits in motorcycle racing for the Auto Union, Lang, prior to his racing debut, was in fact a mechanic for the Mercedes-Benz team. Both became world champions – Rosemeyer in 1936 and Lang in 1939. Yet both remained men of the people, and shared their successes with those fans. To some extent, they opened racing from a sport of one dependent of wealth to one dependent more on talent. This highlighted the demands that were increasing on the sport. Only a few years earlier, the winner would not necessarily the fastest car or driver, but the car and driver combination that could survive the distance. As mechanical breakdowns became fewer and the speed of the car increased, the rigors of driving became greater, demanding much higher performance from the pilot and machine combination. The ever increasing speeds also increased the danger to man and machine – “individual exploits involving…racing cars promised stories replete with high drama because of the dangers that characterized motor races†. Through their accomplishments in taming the rapidly advancing technology of the time, racing drivers captured headlines by waging international technological battles, earning them near super-human reputations. This series of developments heightened the appeal of the sport to the public and opened racing to new markets, while further increased the demands on those drivers as the speeds and expectations. Rosemeyer was, when he died, a national hero and a star celebrity for the country. “A great loss for us†noted Joseph Goebbels in his diary after his death – signaling Rosemeyer’s importance to the government as a star figure .

In the background of these developments, however, more and more teams, and especially private drivers, sought other venues to race competitively, as German participation had precluded nearly all competition. As a result, increasingly between 1936 and 1938, teams such as English Racing Automobiles (ERA) and Alfa-Romeo took to the less spectacular and significantly less expensive 1.5 Liter competitions. While it did not capture the headlines of the big Grand Prix cars, it nonetheless offered a venue where victory by one team – or one nation – was not assured.

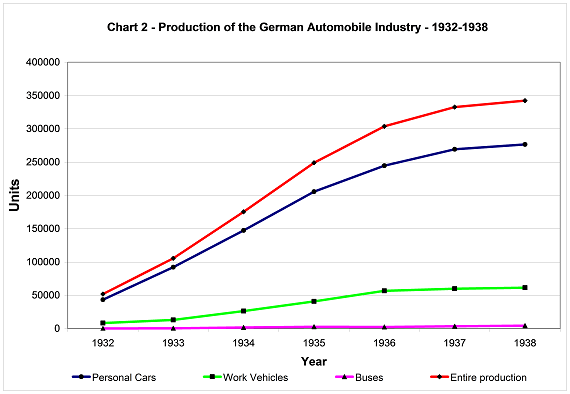

Ironically, this new series of victories also came in the face of substantial problems mounting for the automobile industry as a whole. After 1936, the German automobile industry was experiencing notable raw material shortages; both Neil Gregor and Fritz Blaich are able to show that the problem of the automobile industry not being able to meet demand in the last few years of production stemmed not from lack of productive capacity, but from lack of ability to use that capacity. This was mainly due to shortages in steel and rubber, among others. Noted Blaich, “[from] 1936 all German motor manufacturers had to face the fact that demand for their vehicles grew out of proportion to productive capacity, which was then limited by a rigid rationing system†. Gregor contends that the shortage of automobiles in the mid 1930’s despite hugely increased demand over the 1920s can be seen as “less a product of real consumer demand outstripping capacity than a result of gearing economic policy towards pursuit of the regime’s primary goal – rearmamentâ€.

Wherever the reason lay, the effect of increased delivery times and shortages of raw materials had definitely been noticed and felt by the companies. Auto Union noted that race cars were no longer having the effect they once had in sales both domestically and abroad, due to shortages in materials and increases in delivery times. On this basis, they asked the Reich to further assist their racing endeavors. Whereas only years before it claimed that racing had directly affected sales in measurable ways, the company now suggested that the areas that racing benefited were more of the general economic and political types.

“We must here point out the fact that in the present material and supply situation, a sales- enhancing effect of any race wins at home no longer exists. It should not be mistaken that for the export of our vehicles the advertising impact of racing is successful, particularly those victories that are generated abroad. but it is also a not fully exploited because of the export restraints existing. It follows .. the fact that the time spent by the individual companies for their race participation means economically very limited success for these companies and therefore is more substantially the successes of the German victories in the political and economic field.”

This was not necessarily a true change in the effects of motor car racing, but rather a shift if how they were effecting the German teams, who became increasingly incapable of capitalizing on the success of their cars due to shortages in materials for civil production. As early as 1937, Dr. Kissel from Daimler-Benz was noting that shortages in raw materials were already having negative effects on production and delivery. Specifically, he noted that an increase in the price of rubber wares would thereby increase the price of each vehicle around 18-20 RM, and further that the threatening developments in the steel and iron industry would have negative effects on the industry – perhaps returning it to a period of crisis.

To some extent, these letters can be seen as exaggerations by the companies to gain further support for their companies; in the example of Auto Union, for its race program, and in the example of Daimler-Benz, additional resources and raw materials for the company to capitalize on production while keeping prices down. Despite questionable motives behind their contact with the government, the companies certainly had a point; growth of sales were slowing domestically as demand outstripped production into 1937.

Source: information compiled from DaimlerChysler Archives, Company Report December 1938, p.3

The chart shows the rapid growth of both the entire industry and the personal car sector, while after 1936 there is a clear shift as personal cars and work vehicles both flatten out, an indication of the effect of shortages in raw materials and increases in delivery times. This overall shortage and inability to meet demand was the direct result of the military buildup in Germany, as noted by Daimler-Benz in 1938, when it indicated that vehicles and motors that it could be exporting were instead being diverted to national defense. It was not only shortages in raw materials that were causing problems for German exports, however. On several occasions, both Auto Union and Daimler-Benz note the difficult political situations and currency exchange issues that were hampering their ability to export cars effectively – to name but one occasion, Dr. Kissel contacted the Reich economic minister to inform him of the difficulties now presenting themselves to the exportability of Daimler-Benz products and the chance that exports would no longer increase as they had before. He also noted firms that firms who had not before participated in exporting would not necessarily feel the same effects, in nearly a direct reference to the Auto Union company.

Why would the German government continue to approve allocation of precious resources to the superfluous racing of automobiles when the automobile industry was at the edge of a crisis? The answer was twofold; first, as we have seen, the German government had strongly connected itself with the automobile racing in order to then be able to utilize the victories to bolster national pride as well as international reputation. The second reason was more pragmatic; the German government badly needed foreign currency to continue its military buildup: race cars provided that currency through assisting exports. Blaich further noted “German exports…were encouraged because of the urgent need to obtain foreign exchange; on world markets only hard currency was able to purchase those raw materials which the regime sorely required for rearmament†. However, the same government had hindered exports by severely limiting imports to counter a huge imbalance in foreign exchange from the 1920s. As a result the German government had to widen the appeal of its products and diversify into new markets, and racing offered the perfect opportunity to do this. Races conducted in places such as Carthage, Tripolie, Brno, Pescara, Budapest, Livorno, Rio de Janeiro, Pau, and Belgrade saw the Silver Arrows display overwhelming superiority in completely new markets. How much of an effect did racing have on the perception of the public? In 1938, The Motor proposed a national subsidy to develop a British Grand Prix car to compete with the German manufacturers.

“The proposal is not to advertise or assist the sales of any particular British car, but to reestablish the prestige of this country in neutral markets where Germany is driving out British cars, mainly because its supremacy in international racing is taken as an indication of general engineering superiority.”

Such dominance over neutral markets allowed Germany to continue exporting cars to such markets until the outbreak of war. Indeed, many of the documents regarding racing cars that were sent to the government towards the end of the 1930s included export figures or increases that, theoretically, the company was linking directly to racing.

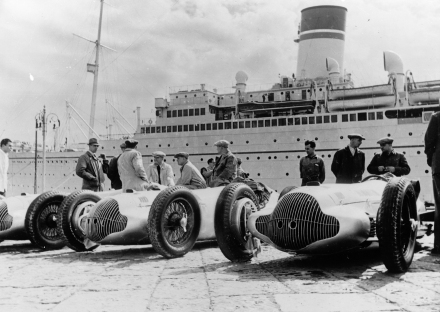

The 1938 Mercedes-Benz W154s arrive in port

Amazingly, though, the Silver Arrows themselves didn’t necessarily have to race in order for the companies to feel their effects. In some cases, the cars were sent to areas where there were no races. The most notable occurrence of this was in Holland, where Auto Union sent one of its race cars to a motorcycle race in Holland, specifically as a means of generating propaganda. The cars were also used repeatedly as propaganda at the yearly automobile shows held in Germany. After race wins, the cars were placed on display; for example, after Bernd Rosemeyer’s win at Donington Park, England in 1937, the car was placed on display at the Auto Union dealership in London. It was notable, however, that the best results in these efforts were achieved when the cars were presented with their famous drivers; anything short of the most famous names in the sport would see reduced effects; of course, this was because the car alone had not won the race, but rather the conglomeration of the driver and machine. To that end, the most successful and notable drivers were preferred for such publicity:

“As for the driver issue , both Hasse as well as Müller (ed. Auto Union drivers) in Holland are completely unknown names and the value of the whole thing is irrevocably reduced to a fraction with posting one of these two drivers.”

Still, as rearmament sped up, race cars – and more importantly, race car wins, were producing less tangible results for the companies. Perhaps the more interesting question is why given the market situation the companies continued to heavily invest in racing. The answer was, simply, that neither could afford to give up in the face of the other’s competition. To do so would have conceded defeat and negated the large amount of effort the companies had put into linking their production vehicles with competition vehicles. It would also present the remaining company with an unfair advantage. This development would push the next evolution of the Silver Arrows, as the designers were faced with developing more extreme demands on their designs and increasing limitations in every direction.

Thus, despite mounting problems in utilizing productive capacity of the automobile industry, in general racing was still paying off for both the German government and the manufacturers participating in racing. There were, however, exceptions to the rule – cases where the government’s desires of complete supremacy over Europe drove racing beyond a reasonable point of profitability for the companies involved.

The 1935 Auto Union team cars – including the early Type B steamliner – are shown at a public exhibition

End Part Three

-Carter