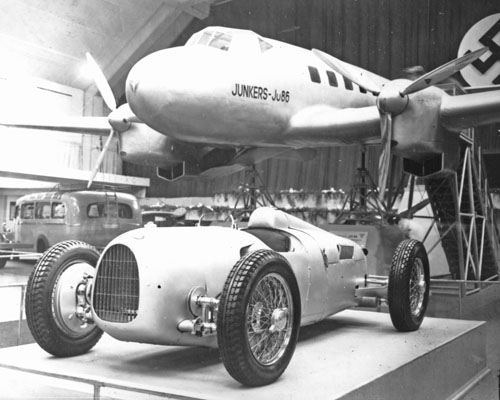

A 1936 Auto Union Type C sits below a similarly streamlined Junkers JU-86 at an exposition

As we saw in the last few installments, Daimler-Benz and Auto Union had heavily engaged in racing – a massive investment for both, pushing the boundaries of existing technology and redefining how motor racing was to be undertaken. The question in today’s installment was who this methodical approach to racing benefited the most. Was the government’s investment in racing worthwhile? Was Auto Union’s gamble on building an unconventional race car a success? Were the extremes to which Daimler-Benz was willing to stretch its racing budget realized in results over the competition? Today we look at some of the more pragmatic reasons behind the motivations of both companies and some of the ideology behind government which helps explain the involvement of both.

Link To Part 4

FIVE: FOR COMPANIES, GOVERNMENT, COUNTRY?

Through their victories, the Silver Arrows, international ambassadors of the German automobile industry and German technology, served many purposes. As we have seen before, there were tangible and intangible results of Grand Prix victories. These results ultimately benefited the companies, the government, and the country.

In terms of tangible results, it was undeniable that the victories of the Silver Arrows had benefited the reputations of their firms internationally, as well as domestically. This was perhaps more glaringly the case with Auto-Union, a group of relative unknowns who banded together to form a much larger company to survive the economic downturn. Racing was not a part of the company’s heritage, unlike that of Daimler-Benz. Yet, by 1937, only three years after beginning racing, they had forged a reputation for speed and success through their Grand Prix victories.

The entire 1934 Auto Union team celebrates a victory

“The name of no foreign manufacturer is better known than Auto-Union. The racing cars that were champions of Europe last year and which have achieved the amazing velocity of 248 m.p.h. on a normal road have won for themselves an imperishable place in the motoring hall of honour” claimed The Motor in a 1937 review of the Auto-Union model lineup . For its part, Mercedes would hearken back to its previous racing success in advertising, claiming that three generations had purchased Mercedes-Benz cars as a result of their racing success, because “[such] success has always been the basis…for further achievements and developments which…have proved the greatest service towards constructional perfection of the car…â€. For both companies, the desire and reality of public perception had been joined. However, the victory in reputation, both internationally and domestically, was won by the Auto Union company. Despite fewer overall wins than Mercedes-Benz, the mere fact that Auto Union could now be mentioned in the same sentence as Daimler-Benz, with its long and illustrious history, was justification for its participation in racing. Auto Union, though today identifiable through the four rings that are mounted on Audis, is mostly remembered for its Grand Prix successes in the 1930’s – by racing and being victorious, Auto Union secured its place in the ranks of motoring fame.

Both companies markedly increased exports over the period of racing. For Auto Union, this meant that the company contributed 27% of the entire vehicle exports of Germany in 1938. Not to be outdone, Daimler-Benz claimed in a letter to Reichverkehrminister Brandenburg that “Our exports have increased in 1937 in value by 60% over the previous year 1936; we achieved for approx. RM 45 million†. This export, it is important to remember, benefited not only the companies in initial sales, but also the government in its quest to gather foreign currency to bolster its lack of raw materials. The benefit here was to both company and government, though arguably the ultimate results of the government’s plan did not benefit the country. The increases in exports coincided with huge production growth at both companies, though it should be noted that this was more an industry wide trend following the depression years than an attribute solely belonging to the two Grand-Prix firms. Despite this, Grand Prix racing had an effect of some degree on the overall industry. This was shown in 1938, when growing difficulties limited expansion of the home market worth to only 14%, foreign exports still managed to still increase 36.5% over the previous year.

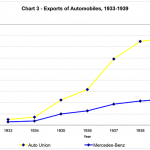

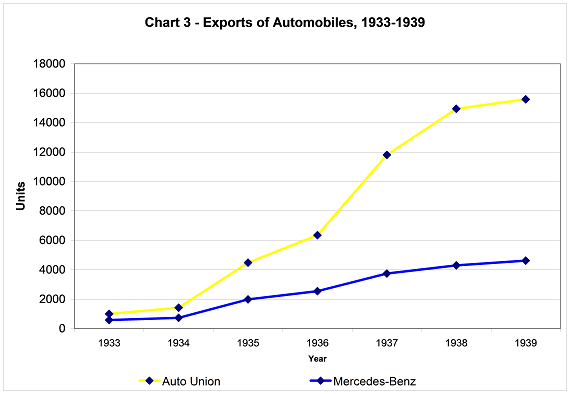

Even given the increasing political tensions and serious strains on raw material supplies, both companies managed to increase exports of automobiles up until the war broke out. The slowing increase occurs notably later and in the face of decreases for Auto Union in the home market in 1939 (Refer to Chart 3, p. 51). Also, it is of note that this chart only accounts for automobiles, and not for work vehicles (Daimler-Benz) or motorcycles (Auto Union), which were staples of both companies, respectively.

Source: Auto Union figures : Erdmann, Thomas, Hans-Rüdiger Etzold and Ewald Rother. Im Zeichen der Vier Ringe, 1873-1945, Band 1 (Weinsberg, 1992), p. 270 (chart). Daimler-Benz figures: Noetzel, p. 98 (chart)

The companies had always claimed that racing advertised German products and increased exports; for example, in 1936 Auto Union had planned a trip to the United States:

“The participation of German companies will undoubtedly represent in America an excellent advertising opportunity for Germany and also assist the sale of luxury cars in German circles (ed. to German immigrants) for the company in America.

However, this was certainly a small market – there had to be more tangible results for these race expeditions to increase exports, and there were. Victories of Auto Union Grand Prix cars in South Africa and Auto Union’s DKW Motorcycles in Australia opened up new markets for the company, which it was able to capitalize on the following years. Soon after the race in South Africa, Mr. Hoffman, Leader of the Landesverbandes Weser-Ems, sent a note to the Auto Union company which stated:

“To my delight, I hear also that the AUTO UNION car name asserts itself more and more with the Germans in South Africa, and I wish you and the Germans that the victory of your drivers will continue to promote the sale of German cars.”

In its company report section on racing in 1937, Auto Union noted:

“It began with the double victory of our drivers Delius and Rosemeyer in the Grossvenor Prize in Cape Town, South Africa, a success which did not miss its beneficial effect on our South African exports.”

Further, in 1938 company reports on exports noted:

“The increase in our export sales – not least due to our racing operation abroad – as in previous years. We mention as an example the motorcycle racing expedition to Australia early in 1938, which could successfully promote the expansion of our Australian motorcycle business.”

Auto Union Type Cs of Rosemeyer and von Delius line up in South Africa

How much had these races actually affected sales? By 1938, South Africa represented the second largest country to which Auto Union cars were exported, behind Sweden. In Australia, automobile sales in 1938 increased 825% following the victory signaling the introduction of the German name, while motorcycles exports increased 92% in South Africa and 135% in Australia. In automobile sales amount increases, Australia and South Africa led the company’s chart. Indeed, with total sales of over 4,000,000 RM in South Africa, the country now represented the third largest export country; meanwhile, Australia became the eighth largest motorcycle-export country, with around 100,000 RM in exports. These were cases where the introduction of a new name through racing had been successful, as had the idea of brand recognition – as Daimler-Benz had stated earlier, successful entry into foreign markets was impossible without propaganda. Auto Union had achieved that propaganda through racing, and had successfully entered two new markets in part by showing the supposed superiority of German technology on the race track.

There were further advantages linking the companies to racing, however. Both Daimler-Benz and Auto Union became leading suppliers to the government and armed forces.

“In due course, the Auto-Union became one of the major suppliers to public authorities and the armed forces. By 1937/1938, this market had reached a volume greater than civilian sales of Audi, Horch, and Wanderer taken together.”

Kirchberg further noted that even though raw materials were lacking and delivery times of vehicles were months to years behind, the military was given top priority in orders. Neil Gregor similarly noted at Daimler-Benz that military production accounted for anywhere from 45-65% of total turnover from 1936 to 1939. True, the entire economy was shifting towards re-armament; however, Auto Union and Daimler-Benz had linked themselves and their production to the government through racing. Perhaps this tenuous relationship can best be seen through the experiences of Hans Stuck. Again, a friend of Hitler’s regime, Stuck’s release from the Auto Union team for various reasons caused alarm in the Nazi party.

“The Reichsführer was very surprised and upset that Stuck should be treated in this way and, as a personal favour, asked that Stuck be included in the team and given a proper contract. If this was not done…Himmler would see to it personally that the SS and the entire German police force would never again order any cars made by the Auto-Union concern.”

Here, racing became somewhat of a liability for the company, as it had lost some autonomy in its decision making process to the government.

However, racing also can be seen to have brought benefits to the companies regarding the government, as well. Daimler-Benz also profited through development of its aero-engines. While development of the Daimler-Benz “601” aero engine had been forbidden by the Reich Air Ministry, Daimler-Benz continued its development, resulting in the new “603” unit presented to the Ministry in 1939. Despite initial Ministerial displeasure, the increase in performance was noted as beneficial to rearmament during the war.

However, the “603” unit was also earmarked for a high priority of the Reich, and indeed Hitler: the T80 World Speed Record car. Increases in the world speed record by the British led Dr. Porsche, designer of the car, to call for increases in horsepower of the engine – in the space of seven months, the requested power output of the motor hugely increased from 1650 PS to 2500 PS. The T80’s increasing demand for power represented a perfect excuse for the company to update the “601” even though they had been ordered not to. Development of the motor was generally in the interest of the company, as it stood to gain contracts from the military with a superior engine design. While the resulting engine did not provide the power the T80, it did become the engine of choice for the most prolific German fighter, the Messerschmitt BF-109. Such development, noted Pohl and colleagues, showed relative self-determination at Daimler-Benz. This could be partially attributable to the company’s success in racing and willingness to participate in projects such as the T80. Having for so long flown the flag for Germany domestically, and more importantly abroad, the companies had a bargaining chip. Certainly, as one of Germany’s leading aircraft engine producers by the start of the World War yet still in competition with firms such as BMW and Junkers, Daimler-Benz would have gained valuable knowledge of low level-running conditions of the T80’s engine. It was undoubtedly one of the reasons that in the contract for the T80, they stipulated that a company mechanic must be on hand at all times to monitor the engine. Such a unique opportunity for the company would present it with an advantage over other companies – such as Junkers, in further development of the engine as a future military power plant for the Luftwaffe and the Reich Air Ministry.

There is another facet of the T80 project that deserves consideration, however – the aforementioned growing need for distinction between the two companies. As sales slowed and the companies felt less of an effect from their expenditure in racing, the need to distinguish one marque from the other represented the next natural step. Here was some explanation for the T80 and the W165 projects at Daimler-Benz – they offered areas to race where the Auto Union was not present. Auto Union immediately recognized the threat of the W165 race car, noting that it represented a step taken by Benz to gain an advantage over its main competition, Auto Union. With this threat, the distinct possibility existed that Daimler-Benz would switch to 1.5 liter racing altogether, a development that the company took seriously:

“So we have to decide if we want to retain a) by immediately addressing the accelerated construction of a 1 ½ ltr.- race car following the on-going development of the car racing or b ) the further development still want to wait , despite the danger necessarily , then may losing touch for some time, which in my opinion but would a significant loss of prestige for the Auto Union.”

Ironically, it was specifically the Auto Union that held the advantage over its rival. Though Auto Union might not have been ultimately as successful in the Grand Prix, it was heavily involved in motorcycle racing, and had accrued great success on that front. The combination was unique – only Auto Union competed in both Grand Prix motorcycle racing and Grand Prix car racing. It was to its advantage, and the company was careful to note this in letters to the government and reports, underlining (literally) that Mercedes-Benz only took part in car racing:

“There should be no doubt that the Auto Union participated in the German automotive industry in much the strongest ground at the power sports and making appropriate financial expenses, because during the same period Mercedes-Benz (Ed. – underlined in original text) only involved themselves in racing cars sports and reliability tests for car,NSU only racing events and reliability trials is charged for Motorcycles, Auto Union maintains a race car and racing motorcycle sport without elude the other events, while all the rest of industry expressed only on a case by case basis and in relatively small to the extent of participation in reliability tests their sporting interests.”

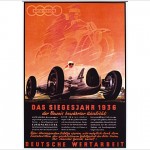

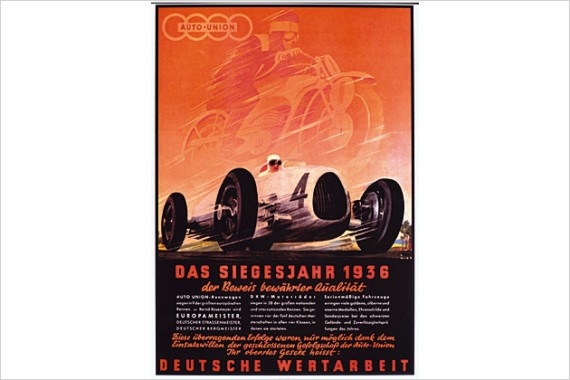

A 1936 Auto Union victory poster shows not only their successful Type C, but a DKW motorcycle in the background as well

Grand Prix racing also hugely benefited the government, as had been planned. The records and race victories established international prestige for not only Auto Union and Daimler-Benz, but more importantly for the government and for the entire country. This can partly be attributable to the foreign press. From the outset of racing in 1934, the British press referred to the two teams as ‘The Germans’. Exactly as had been planned, the two teams’ participation and more importantly their success led to an increase in the international prestige, noted by the British press. British experts, in fact, often claimed that Grand Prix racing wasn’t necessarily beneficial to the company: “If Grand Prix racing were a serious factor in the sale of popular cars, all manufacturers would be forced to it†, yet Opel, the largest automobile manufacturer in Germany, did not participate in any sort of racing. But another British expert pointed out that all manufacturers of the country did not need to take part; benefits were industry wide:

” [the public] obtained the impression – and who shall blame them? – that the German motor cars are invincible and that Germany obviously builds good cars. Then, when Germany begins exporting large numbers of her ordinary products…they sell on the prestige obtained for them by the Government-subsidized German racing cars.”

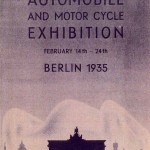

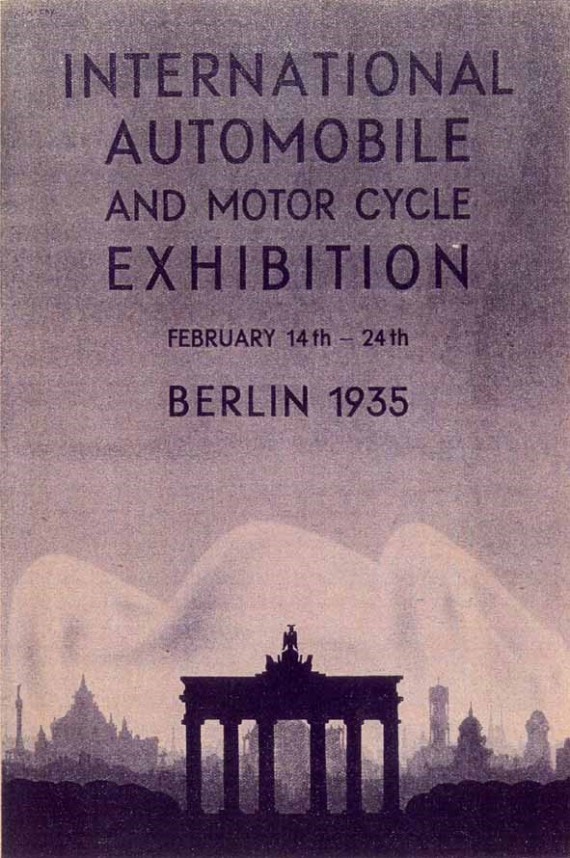

From this point of view, the government’s idea of supporting racing in order to improve the whole industry had worked. The cars were the international representation of Germany’s motoring ambitions; a 1935 International Automobile Exhibition poster for Berlin depicted a stylized Grand Prix car looming over Berlin (See Figure 2). At the same time, the drivers combined with the technology to fulfill the new vision of modernity within the Nazi ideals;

“the Nazis selectively appropriated and promoted innovative technologies and sciences…in the pursuit of political objectives, including enhanced economic output, racist policies and warfare, all of which party officials considered ‘modern’.”

Figure 2: The image of a Grand Prix car looms above the city of Berlin and the Brandenburg Gate in a 1935 International Automobile Show advertisement. Source: The Motor, 5 February 1935, V. 67, p. 37

Racing exploited all of these hopes and aspirations – it placed Germans in the most advanced German technology into an economically beneficial situation where they participated in a ‘battle’ between nations in an international arena. “In this context…motor racing formed part of a wider culture of high-speed competitions…in all of which individuals handled fast machinesâ€. Government interest in racing was for this reason a forgone conclusion. Indeed, apparently the government thought it was the people’s concern, as well. Racing was representative of the future of national defense in the eyes of the government; it was the most modern expression of the combination of technology and humanity. Heidrun Edelmann noted this in her appraisal of the development of motorization in Germany:

“Later it was [the NSKK’s] primarily goal to provide an understanding of and deepen the need for the engine and its tremendous interaction on the defensive strength of the nation; and the regime made no effort to conceal these paramilitary purposes. Because the ‘national defense’ requires an ‘absolute unity of man and machine’, racing was given high priority. To the ‘heart’ of all efforts in this regard was the ‘youth motor exercise’ applicable; it was necessary ‘for the most part already existing natural enthusiasm’ of youth for ‘motorcar’ to steer towards the ‘right track’. The Nazi propaganda was speaking openly what 1937 Sopade (Social Democratic Party – the author) report stated: ‘The boys are indeed enthusiastic, but it is not the idea of ​​National Socialism, which deeply inspired, it is the enthusiasm for the Sport, for the technology … National Socialism has understood it to be excellent, meet this already existing interest in the youth in all technical and organizational matters and to make available this interest for its own purposes’.”

How much had this benefited the German automobile industry? Edelmann was able to show that starting at a relatively similar position, the automobile industry quickly outdistanced other German industries in terms of growth. With the pre-crises high of 1928 establishing the benchmark for production, in 1933 the automobile industry was operating at 80.9% of this figure, while the general industry was at 65.5%. By 1937, the difference was notable – the automobile industry was at 242.4% of its pre-crises production high, while the general industry was only at 116.8%. Some research on the automobile industry has focused more on the difference between the automobile industry and other major industries, and supports the thought that the automobile industry was not truly outgrowing her rivals under National Socialism, but rather experiencing a period of rapid growth which the others had previously experienced:

“The chemical, electronics, optical and coal industries all developed rapidly under Bismarck and provided much of the basis for the German economy’s expansion in the Wilhelmine period. The German automobile industry did not begin to develop until the Weimar period and did not significantly expand until the Nazi period.”

“The industry, in aggregate, generated the second largest income from sales after coal miningâ€, noted Simon Reich when considering the remarkable growth of the industry between 1933 and 1939. In a comparative chart of production for Germany industries by Richard Overy, the automobile industry (motor cars and commercial vehicles) showed its relative growth to other industries (Refer to Table 2 and apologies that these charts do not transfer well to the page):

Table 2 -Index of production of selected German industries 1928-38 (1928=100)

Industry: 1932 1933 1935 1938

Coal 69.4 72.7 94.8 123.0

Pig Iron 33.3 44.5 108.8 154.3

Steel 39.3 52.2 112.6 162.2

Motor-cars 28.6 59.7 136.1 200.7

Commercial vehicles 22.9 40.7 121.7 200.7

Electrical energy 76.5 83.7 116.3 175.9

Machinery (on order) 32.8 39.1 111.8 166.7

Chemicals 50.9 58.5 79.5 127.0

Shoes 85.3 101.5 101.7 118.5

Textiles 79.2 90.5 91.0 107.5

Household goods, furniture 69.6 70.5 80.4 113.6

Source: Overy, Richard J. The Nazi Economic Recovery, 1932-1938. (Cambridge, 1996 [1982]), p. 53 (Statistisches Jahrbuch für das Deutsche Reich 1938 [Berlin, 1939])

The chart would seem to agree with Stahlmann’s conclusion, that the automobile industry lay far behind other industries in the 1920’s, and was then playing ‘catch-up’ in the 1930’s. Perhaps more striking, however, was the relative growth of the German automobile industry when compared to other motorized nations (Refer to Table 3):

Table 3 – International Automobile Production (Thousand Units)

1932 1938 Increase

1) United States 1,369 1) United States 2,691 97%

2) Great Britain 233 2) Great Britain 448 92%

3) France 172 3)Germany 342 560%

4) Canada 61 4) France 207 20%

5) Germany 52 5) Canada 164 170%

6) Italy 29 6) Italy 69 138%

Source: DaimlerChrysler Archives, Company Report December 1938, p. 3 (chart)

While this development certainly can’t be totally attributed to the racing of cars over the same period, it is nevertheless arguable that racing played an important role in helping the country achieve such impressive gains. Germany was still playing catch up to her more substantial rivals Great Britain and the United States, but in just six years after the worst crises the industry had seen, the gap between Germany and other motorized nations had decidedly closed. Though the United States still lay far out of reach, Germany had importantly outperformed her European rivals. Germany did lead other nations in one overall number, however; motorcycles. Due to the taxes that had hampered car sales in the late 1920’s and early 1930’s, motorcycles had increasingly become a staple of the German culture, a point that Auto Union noted in its company reports. The company, whose DKW range was the largest manufacturer of motorcycles in the world, counted over 1.5 million motorcycles in Germany in 1938, compared to 450,000 in England and only around 100,000 in the United States. This development, the company explained, was an aspect of the will of the people to motorize the nation. Motorcycles represented an economical way in post-war Germany to satisfy this ‘will’ of the people:

“Of particular interest here is the high stock of bikes in Germany , 1,582,872 units in 1938 , while at the same time in United States just a motorbike stock of approx. 100 000. piece in England of approx. 450,000 motorcycles was recorded . This fact clearly demonstrates the strong existing in Germany , supported by the broad strata of the population will to motorization , but the piece moderately particularly strong impact in the use of the motorcycle due to the overall economic situation in Germany in the postwar period.”

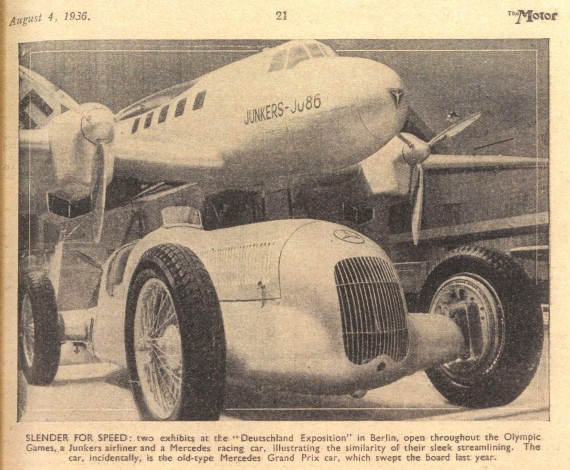

Further, the cars represented the ideals of the government; German superiority in every aspect. In the international stage of the Olympics in 1936, when the country was slated to display German dominance, a Mercedes-Benz W25 Grand Prix car sat next to a Junkers Ju-86 airplane, linking Germany’s current dominance on the land with her impending dominance in the air (See Figure 3).

Figure 3: Mercedes-Benz W25 and Junkers Ju-86, Berlin ‘Deutschland Exposition’, 1936. Source: The Motor, 4 August 1936 : 69. p.21

If the Olympic Games were intended to highlight the inherent superiority of Germany over her rivals, the Silver Arrows were the automotive realization of that goal. The Olympics displayed that the Germans were not ‘superior’ in ever aspect; despite this, the race cars continued to thoroughly dominate their competition.

The government was understandably eager to display this superiority. As the mighty Zeppelin airships had only years before, the racing cars of Germany had become her international ambassador of both modernity and superiority. This, in turn, benefited not only the companies, but the industry, the government, and the country as a whole. It also highlighted the increasingly complex and interdependent relationship between the cars and the government – from merely participating to bolster car sales, racing had grown to be including into ideologies of superiority as had most sport and competition in Germany. The companies, reliant on the support and funding of the government, had no choice but to accept this new role. Racing had been transformed from representing sports cars to representing racial ideals by espousing the supposed superiority of German drivers and German technical ability by the government in only a few short years, while simultaneously fulfilling its previous benefits in unprecedented fashion. In 1934 the Völkischer Beobachter claimed before the Avus Race, one of the first to have both Auto Union and Mercedes-Benz participating:

“[ it ] will make a trial of strength between the German and foreign new construction. A major event that determines the power of the German motor industry.”

However, when Tazio Nuvolari won the Donington Grand Prix in October 1938 (shortly after the Munich Crisis), the paper noted: “[ the ] race was the final proof that no other country is able to touch the German superiority in racing cars†. German superiority in race car construction, however, had not been a myth.

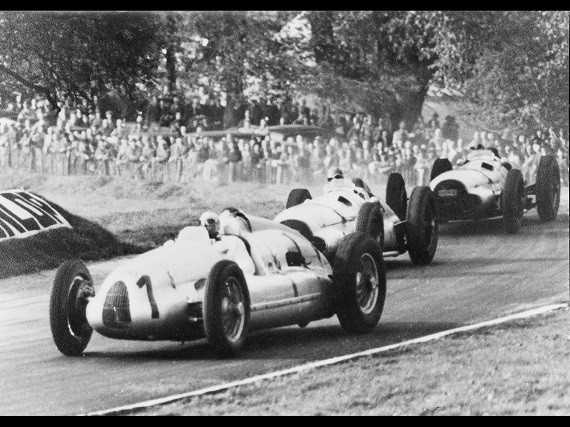

Tazio Nuvolari leads two Mercedes-Benz W154s at Donington in his new Auto Union Type D after replacing Rosemeyer in 1938.

END PART 5

Tune in next week for the conclusion of our Silver Arrows series!

-Carter