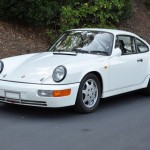

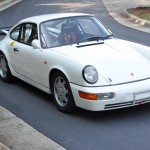

We naturally have a certain predilection toward rare cars here at GCFSB even if most of the cars, especially those made by Porsche, remain well beyond the means of those of us frequenting these pages. But that doesn’t make them any less cool to see. The model we see here, a 1991 Porsche 911 Carrera 4 Lightweight, was one I did not even know existed. The ad description is long, but it does a good job of providing the genesis and details of the build for the 964 C4 Lightweight. To summarize: the interior was completely stripped of everything that wasn’t essential, race seats and roll bar were added, and the weight savings were completed with aluminum front and rear deck lids and plexiglass side windows. Altogether 770 lbs were removed from the car, making it lighter than its rear-drive brother the Carrera RS. Mechanically, these were fit with an AWD system derived from the 953 Paris-Dakar rally car with controls to adjust the differential bias front to rear and left to right. A single-plate clutch, light flywheel, and shorter gear ratio would help deliver the power, and power itself was up to 265 hp in standard form (the example we see here is said to have an uprated version of the engine producing 300 hp). The 964 C4 Lightweight was in almost every way a racer designed simply to meet the demands of some enthusiastic collectors. What is perhaps the best part: from the outside the C4 Lightweight looks like a 964 with a whale tail and lowered suspension. There’s very little to suggest everything at play here. It’s wonderful!

CLICK FOR DETAILS: 1991 Porsche 911 Carrera 4 Leichtbau on Classic Driver

Year: 1991

Model: 911 Carrera 4

Engine: 3.6 liter flat-6

Transmission: 5-speed manual

Mileage: 5,493 km (3,413 mi)

Price: Inquire

Serial Number: 964012 (1 of 20)

– Grand Prix White with black interior

– 5,493 original kilometers

– Featured in an internationally famous Porsche Collection

– Technical features:953 Paris-Dakar AWD transmission, mechanically variable differential lock controls, D-90 magnesium wheels, Carrera RS seam welded body shell, sport steering wheel, aluminum body panels, Matter cage, lightweight glass, fire system, with a very low body weight of 1,100 kg. M64/01 engine which produces 300hp.In each decade since Porsche introduced the 911, it has created a very limited series of competition cars that won events and enhanced the company’s reputation. Decades later, these became highly desired trophies for knowledgeable collectors. The 911R (all 20 plus the four prototypes) came first in 1967/1968, followed by the 1972/1973 911 Carrera RS 2.7 Homologation cars (just 17 of those), with the 1984 911 Carrera SC-RS (with 20 originals) appearing next. Since its earliest days, Porsche had sold its “used†competition cars to help fund the next series of racers. No one conceived of inventing a racecar as an instant collectible. But then at the end of the 1980s, outside factors intruded and things changed.

In late 1988, customer sports department manager Jürgen Barth took an idea to competition director Peter Falk. Porsche sales were seriously depressed due to the international exchange rates. The world’s stock markets had crashed in October 1987, and recovery was slow. This affected customer racecar sales as well and Barth sought a project to re-energize customers. As customer sports department manager, he proposed assembling two or three rear-wheel drive 964 RSR racers using 3.4-liter engines for the 24-hour endurance race at Nürburgring. Years earlier, Norbert Singer had created a graphic presentation that demonstrated when Porsche raced, sales increased. Falk knew Singer’s data and gave Barth tentative approval for the RSR endurance cars and for a second idea as well. That was to create a strictly customer car on the new platform to use up some exotic spare parts Weissach had sitting around.

Typically, when Porsche develops a new-technology racecar, it doesn’t merely construct the few examples that other competitors and the public see. For the 1986 Paris-Dakar 953s, Porsche had assembled three cars. Yet about 30 sets of all-wheel drive running gear were left over. With its high clearance, the Typ 953 strictly was an off-road works entry. But Barth envisioned perhaps half-a-dozen new cars with lower ground clearance for circuit racing.

Current competition regulations offered no venue where this all-wheel drive racer could compete, however Barth had watched Porsche’s influence operate in the past. He knew if the company pushed it, opportunities and series had opened up. However, these were different times, better times, and worse times. It was the accident of timing that made this car interesting, its story relevant, and its lessons important.

In the U.S. and throughout the world, those who weathered the 1987 market crash without needing bankruptcy protection looked for new ways to work their money. Successful business people always have collected trophies and though Porsche’s dealers had trouble selling cars for $60,000, “investors†with no racing interest or experience were buying 908s for $400,000 one week and selling them for $700,000 a week later. Prices, if not values, were soaring. Legitimate racing cars, even those with no competition history, had become the new investment target.

One more element made Barth’s idea timely. In Washington, the EPA and DOT had clamped down on the grey market auto industry in 1987, enforcing rules they previously had treated less vigilantly. Red flags went up because an increasing number of 1973 RS 2.7s entered the States as racecars though seemed to have full interiors, carpeted trunks, and not every one had a roll bar. This had tripped up PCNA’s efforts to import 959s and provoked official distrust at the sight of any Porsche. As Californian Kerry Morse put it years later, “You can’t bring a car into the U.S. with a seventeen-digit serial number, a roll bar, and air-conditioning and call it a race car. The folks at the EPA and DOT are not stupid.†Ironically, this contributed to the racing car investment frenzy.

Morse knew the federal agency people well. He had owned, raced, imported, and brokered many modern and historic racing cars throughout his career. He had witnessed the late 1980s price jumps and understood the significant features that motivated speculators: These cars were purpose-built with ultra-limited production that easily could be verified. And they were importable. He also knew Jürgen Barth, calling on him on every visit to Germany and frequently staying at Jürgen’s home. On a trip in mid-1989, Kerry asked his host what was knew?

Barth explained his idea to gut the 964’s interior and body of all possible excess weight, install 953 running gear and, in essence, create a 964RS. How large a run was Barth considering? Half a dozen? Ten? Morse committed to take the first one. Barth estimated it might go for 200,000DM, about $110,000 at the time. With the first solid order, both men knew it was easier to move a project forward.

Helmut Flegl was number two in engineering behind new director Ulrich Bez. As co-developer of the new 964 Carrera Cup model with Roland Kussmaul, Flegl wondered where this 964RS was supposed to fit in competition. Barth answered each inquiry and pressed ahead, removing close to 770 pounds of weight from the cars. He replaced doors and front and rear deck lids with thin aluminum, and side windows with Plexiglas. He mounted a roll bar in the sterile interior. Two large knurled knobs set off the instrument panel. Porsche racers recognized these as turbo boost controls on 935s. But this engine was normally aspirated, not one fitted with twin turbochargers. For this car (now called the Carrera 4 Leichtbau, or C4 Lightweight) these two matching controls altered differential bias from front-to-rear and left-to-right. Barth fitted a stainless-steel dual exhaust system that delivered a deafening 107dB at 4,500rpm, making it one of the loudest Porsche 911s ever. There was no engine noise protection, no air filter, and no heater fan. Modified electronics and the minimal exhaust elevated engine output to 265 horsepower, up from the production 250. It got a single-plate sintered-metal clutch, short-ratio five-speed transmission, and an ultra-lightweight flywheel. It made a potent package at about 2,430 pounds. Visually the car appeared stock and nondescript. It ran on stock-width tires and wheels, sixes in front, eights in the rear with neither flares nor modified bodywork. Barth had gotten some things accomplished in making his unusual car. Flegl and others in management vetoed others. All this work took months. As the first one neared completion, it got one other significant specification.

“After the situation with dozens of 1973 Carrera RS 2.7s with their full serial numbers, and the 959 debacle,†Kerry Morse explained, “almost anything Porsche did was going to get serious scrutiny from U.S. EPA and DOT. Racecars have six-digit serial numbers. These [C4LW] cars could not come into the U.S. with a serial number beginning WP0ZZZ….†Barth pushed hard for a different number sequence and the cars started with 964001 rather than 964101. They seemed like factory works cars, not customer vehicles.

Word spread rapidly through the small world of Porsche racecar devotees: This was something that might never compete but it was rare and it was available. The run expanded to 21 cars and sold out quickly. The initial four emerged between September and November 1990, as 1991 model year editions. Zuffenhausen delivered body-in-white shells to Weissach where technicians painted them in the race department and installed their modified engines and running gear. Internal politics drove the price up to 285,000DM ($171,690 at the time); some decision makers saw an opportunity to let this odd marketplace pay extra for its exclusive toys. The first one went to a collector in the United States. Cars went to England, Japan, and France, others remained in Germany, and several more came to the U.S. Because the EPA and DOT decided only to admit these cars as racers following individual inspections of each one, U.S. buyers had to take delivery at the factory. This added another 39,000DM ($23,500) in VAT, value-added tax, to their purchase price. They could recover this upon leaving Germany with the car, but suddenly these cars cost nearly $200,000 U.S. This figure was hard to swallow when any of 70 starting-flag-ready 964 Carrera Cup cars – for which a series in Europe and the U.S. already existed – sold for 123,000DM or $73,650. Some people questioned whether 953 running gear was worth the extra $120,000? C4 Lightweight deliveries continued through 1991 but the collector car world was approaching critical mass.

When the balloon burst in 1992, its fallout scattered everywhere. Prices for Ferrari GTOs had reached $25 million, figures formerly reserved for Monet oil paintings or medium-sized islands in the south Pacific. Porsche 908s changed hands for $1 million and deals for 917Ks approached $3 million. Prices had swollen to four times life size just as the sharpest speculators jumped to the next trend. This left hundreds of amateur players holding cars attached to ruinous loans. It affected racing dramatically; the 24 Hours of LeMans, which typically counted 50 to 60 entries through the 1980s, started with just 28 cars in June 1992. Barth had to send letters to buyers reminding them of their commitments.

The last car left Weissach in late 1992. The project made money, as Jürgen Barth’s projects virtually always had done. It had cost Porsche nothing extra to delete sound insulation or to add running gear and a fixed rear wing that it already had in stock. The legacy of the C4 Lightweight became clear: special limited editions including the 1973 RS or even the 1989 Speedsters had strong appeal to loyal enthusiasts. The company learned that its customers were willing to dig deeply in order to be the only one in town with something unique. It was a lesson Porsche has neither forgotten nor ignored.

When it comes to rarity these are tough to beat. Only 20 were made, which I think makes them the rarest individual model of the 964. If we want to get real nit-picky there are variants of the 3.6 Turbo S produced in lower numbers, such as the Japanese-only Slantnose, of which 10 were built, and the US “Package” version, of which there were 17. But that’s really just parsing option packages. As a total build number of the model itself I think this trumps them. So that makes the C4 Lightweight very expensive, especially considering that every one of them likely was bought by speculative collectors and sit, like this one, with extremely low mileage. Also, they were very expensive for their day: consider that for US buyers a C4 Lightweight could cost nearly $120K more than a Carrera Cup. For most of us, the price doesn’t matter. It’s too much. But we can still sit back and marvel at another of the rare 964s.

-Rob

Less is more. I want to drive that car!

The windows and roll bar might be a clue.

Scalded Ape.

Rob, you should double-check your stats- the 964 Turbo S slantnose was not Japan-only, they were sold here as well. Total production is around 40 cars. It’s not a 3.6 Turbo S, just Turbo S. There is no such thing as a 3.6 Turbo S. The “package” cars are referring to the X88 option, which gave you the Turbo S engine with the asymmetrical rear quarter vents and various other upgrades. The X88 is basically a Turbo S slantnose without the slantnose. I think you are correct in stating that the 964 lightweight is one of the rarest 964 variants out there. The Turbo S2 that was homologated for the IMSA supercar series in the early 90s might be rarer, I don’t remember the production numbers. Legit US street-legal 964 Carrera Cups are also very very rare.

@TM, you are correct that there is no model called the 3.6 Turbo S, but there were two different versions of the Turbo S built for the 964, one based off of the 3.3 liter engine and the other the 3.6, so I find it easier to add the 3.6 to help differentiate the two when we lack the other context. As for the Slantnose, the numbers are correct and they were Japanese-only for the Turbo S. There is the Slantnose and the Flatnose Turbo S, which are two different front profiles. There will be a bit more detail on this with the car I’ll feature on Sunday, so stay tuned!

Rob,

Given that I am in the US, I am writing this with a US-centric bias. The 1992 Turbo S was never sold in the US, except as the Turbo S2, as a homologation special for the Bridgestone Supercar series- they made 20 of these cars for the US. The US version also kept the Cup design 17 inch wheels, unlike the Euro version that had the 18″ Speedline 3-piece wheels.

The Turbo 3.6 version that has the M64/50S engine (the “S” engine) is either a X85 flatnose in the US (39 made) or the X88 package car (non flatnose, 15 made for US, 2 for Canada). In RoW, the X83 flatnose has the same fenders, headlights, boxed rockers and vented quarter panels as the M505 optioned, 930S that was made until 1989 (10 made), but with a 964 type front bumper. 27 X84 cars were made, which are essentially the same as the X85 US spec car. There are also the X88 RoW cars (51 made) that are essentially the same as the X88 “package” car in the US.

Technically, all of the non-standard fendered versions of this car were “flatnose,” whether it is in German, English or Japanese. I can see why you would call it a slantnose as the Japanese version looks like an M505, but even the Japanese designation is flatnose.