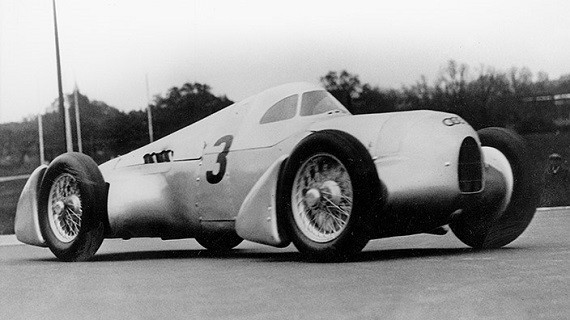

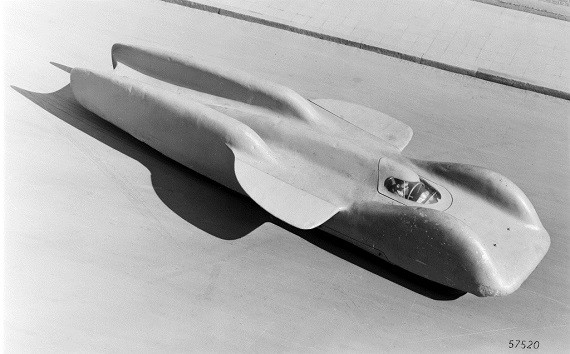

A 1935 Auto Union Type B Streamliner used for both records and the annual Avus race in Berlin

This past weekend weekend we saw a bit of hubris and bad strategy lead to Mercedes-Benz losing to Ferrari in the Malaysian Grand Prix. Despite the massive investment and seemingly pedantic attention to detail, the same problems existed in the 1930s for the company. Increasingly Mercedes-Benz needed to differentiate itself from Auto Union by undertaking extreme efforts. These efforts were not always profitable; indeed, one could argue that – as we saw last week – since they were already having difficulty delivering cars thanks to raw material shortages, undertaking new forms of racing and record-breaking might have seemed ill-conceived for the company. However, still at stake was preferential treatment from the government, especially when it came to lucrative military contracts. As such, Mercedes-Benz undertook some unlikely projects to not only gain international prestige for the Daimler-Benz model range, but indeed to curry favor with the government.

FOUR : PUSHING THE LIMITS – THE GOVERNMENT GOES RACING

The origins of record-breaking with the Silver Arrows were more than likely quite unexpected. In its introduction to the press in March 1934, the first Auto-Union race car (Type A or P-Wagen) set three World Records for speed over distance.

The 1934 Auto Union Type A proudly displays the records set on the sides of the car

According to Nixon,

“[it] is doubtful that either firm learned anything from record-breaking that it didn’t already know from racing, but this was still very much the age of records on land, sea and air and the prestige value was enormous. This didn’t go unnoticed by the Nazi government, which was always on the lookout for ways of proving Aryan superiority to the world, even peacefully, if necessary. So record-breaking was actively encouraged as a means of showing the German flag in this period of extreme nationalistic fervour.”

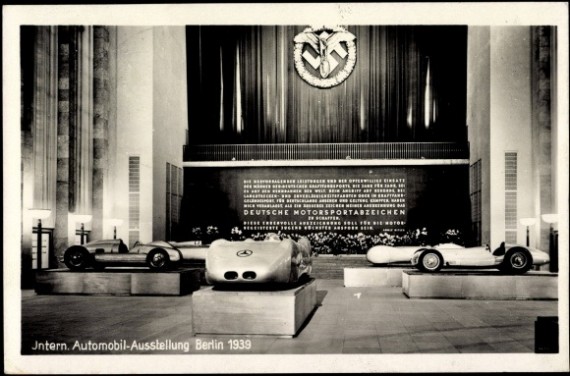

The record breaking that ensued broke ultimate speed records in class and speed over distance, with the super-streamlined Silver Arrows flying into the record books. This culminated in January 1938, during the NSKK-sponsored “Rekordwocheâ€, when the German military officially closed the Frankfurt-Darmstadt Autobahn to allow the cars an attempt on World Records. The result was twofold, Rudolf Caracciola established a new Class ‘B’ speed record at 268 mph, and Berndt Rosemeyer died while trying to best that record. Rosemeyer, having been promoted to SS membership through his racing exploits rather than his political beliefs, was one of the first martyrs of the Nazi cause for international recognition, and as such he received a full military style funeral, and was further honored at the Berlin International Motor show in 1939.

The 1939 Berlin Automobile Show displayed the record setting streamliners from Mercedes-Benz and the older Auto Union Type C car, as well as the Grand Prix cars and a tribute to Rosemeyer

Rosemeyer’s death highlighted the inherent dangers of record attempts and racing in general, and also pointed towards a new destination for them. As plans went ahead with construction of the Porsche-designed, Mercedes-Benz built T80 World Speed Record car, Daimler-Benz notified the government of the shortcomings – literally – of the section of Autobahn near Dessau which had been prepared for the run. In a letter from Daimler-Benz to Hühnlein, the company noted:

“During your last visit to our factory, we have notified you that we fight for the German international recognition to build a world record car … In Germany, the implementation of a world record attempt is impossible because even at the new record stretch at Dessau the starting and stopping areas are too short.”

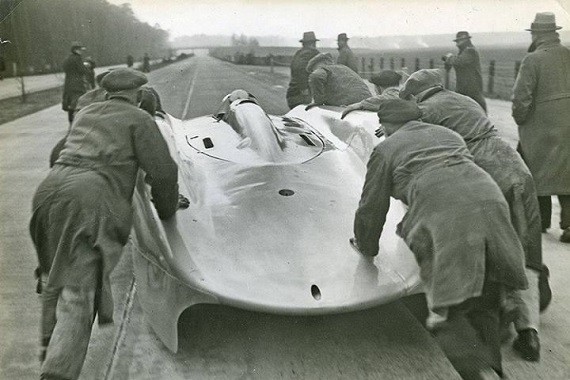

Rosemeyer sets off for a record run on the Autobahn near Dessau. He would die in such an attempt at nearly 270 m.p.h.

This meant, at least to Daimler-Benz and Porsche, that the Great Salt Lake in Utah would be the only logical place to attempt the run. This was the crux of their letter to Hühnlein: that he must prepare to fund a trip to the United States in order to achieve the record. However, Hühnlein’s personal opinion on the matter combined with the international political tension generated by the German military buildup after 1938 relegated such a trip to the drawing boards only. Where the car was to set the record was not the only underlying issue; rather, that lay in the existence of the car at all.

Hitler had proclaimed that records were one way to generate national prestige; “Ultimate world records on water and land – that suits our propaganda needsâ€. Hitler’s desire for world speed records had been realized by the exploits of the Silver Arrows to that point, who held numerous class records – but not the ultimate land, water or air speed records. Those laurels has rested in other countries; the first two with Britain and third with Italy. Hans Stuck, successful driver for the Auto Union team and the same driver who had set the first Silver Arrow speed record, had a personal desire to set the world speed record. However, Auto Union, “already stupefied by the unexpected high costs of its Grand Prix racing, respectfully declined to commit itself to this even more exotic effortâ€. Stuck then called in a series of personal favors: friend Ernst Udet, who happened to be of high position in the Luftwaffe, would guarantee Stuck with Daimler-Benz aero engines (which could not be utilized without Luftwaffe approval), friend Dr. Ferdinand Porsche would design the car, and acquaintance Adolf Hitler would provide the road (at Dessau) for the attempt. Stuck gained favor with Hitler by setting a time/speed records in Auto Union powered boats and race cars as well as many other records for distance, while the Daimler-Benz aero engines intended for the T80 were the engine of choice as they set new propeller-driven airplane speed records for Germany. Indeed, Stuck and Hitler had met as early as 1925, when Hitler had promised to support him racing when he eventually gained power in Germany. Daimler-Benz was backed into a corner; Stuck had already secured the engines of the firm, and with friend Neubauer supporting the effort from the inside, they agreed to construct the record car.

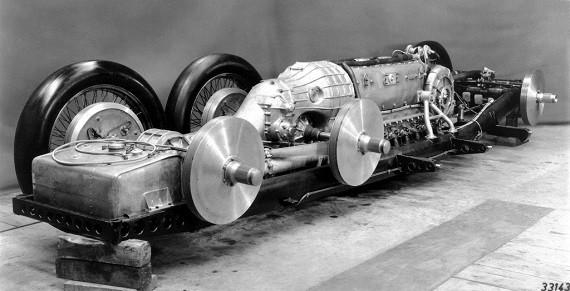

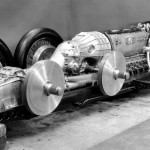

The very un-carlike extreme construction of the T80

The project, ultimately unrealized due to the outbreak of war, offered little value to the Daimler-Benz company. Had the T80 actually achieved the World Speed Record, Daimler-Benz would have added another feather to its cap. However, here was the perfect case of the close cooperation with the government backfiring for the company. Saddled with the huge expense of the T80 project that had yielded no results, Daimler-Benz fired off a salvo of appeals to the government for additional funding:

“For over two years, we have been engaged in the creation of a super-racing car, a world record car. We let ourselves be guided by the idea that, as we have shown in increasingly superiority in all other areas of the automobile, that we could finally conquer the British World Records. We knew that we would act in the implementation of this objective in the sense of our guide and in the interest of our Korpsführers.”

The super streamlined T80 was doomed to failure nearly from the beginning, yet was pursued with active encouragement from the government

While certainly Daimler-Benz had stood to gain prestige for itself by establishing the world record, the national pride which had been associated with Britain’s record holding was likely to be more beneficial to the Nazi government. Kissel noted in his letters that the total outlay for the T80 project was around 600,000 RM as it stood, uncompleted due to the outbreak of war. However, even finished the T80 would have been unlikely to achieve its aim; the decision of the government not to allow the record outside of Germany crippled the project even before it could launch an attempt.

The Reich’s unwillingness to compromise in the last years of peace did not allow any room for negotiation – and would cripple many of its’ special projects. This was true in the case of the T80, because though the natural spot to achieve the record was in the United States, the government maintained that the record must be broken in Germany, as a matter of pride – a German, in a German car, in Germany, would set the record. Though the project never developed sufficiently to press this issue, this position doomed the project before it had even gotten going. It is unclear whether or not Daimler-Benz and the race department were aware of this from when the appeals for a trip to the United States were first launched, or if they only recognized in hindsight that given the political situation, the T80 would not work. Development work pressed onwards into 1939 – yet as the record was continually re-set at higher standards by the British, the hope of setting the world speed record for Germany slipped farther and farther out of reach – not because of lack of ability or a design flaw, but rather because the Reich and its conflicting aspirations had eliminated any hope of success by condemning the car to run at Dessau.

The letters to the Reichsverkehrsminister and NSKK leader Hühnlein also mentioned another project which had cost Daimler-Benz a great deal of money, though with a more illustrious result. This was the W165 race car, a car which had been designed and completed shortly after the announcement that Italy’s races in 1939 would exclude the international Grand Prix formula cars of 3 liters in favor of race cars of 1.5 liters. Italy had no successful 3 liter race cars to compete with the Germans; conversely, the Germans had no 1.5 liter race cars to compete with the Italians. It was a clear maneuver by the Italians to exclude the German teams from competing in their races. This fact was not lost upon the Germans; Kissel commented, that under the new 3 liter formula the Germans had continued their unassailable ways,

“So it was that foreign countries more and more into the background and new ways sought to come to racing success. This included Italy’s attempt last year at the “Grand Prix of Tripoli” finally to win back laurels when it did not allow the new top Formula racing car, but this event invited only 1.5 liter racing cars.”

This reaction was caused by what Kissel termed as extreme jealousy in response to the uninterrupted series of victories by the German Grand Prix cars. As a result, Daimler-Benz immediately began work on a 1.5 liter race car to compete in the Grand Prix of Tripolis. What resulted, the W165 race car, was apparently a successful surprise even to the company:

“This venture succeeded with surprising success … The echo of this unique great success in the world was an overwhelming. As a result, we have served dutifully as a leading company not only for us but the entire German prestige.”

That Daimler-Benz had achieved an unprecedented success in designing two cars to win a series it had never taken part in within such a short amount of time was undeniable; yet, as with the W125 race car in 1937, Daimler-Benz’s path to victory was an expensive one. In order to build the two W165 race cars to win just one race, Daimler had spent 667,000 RM – about two-thirds what they had anticipated an entire season’s racing to cost only four years earlier.

The Tripolis winning W165 finished 1-2 in 1939. It would race only once.

As with the ill-fated T80 project, the W165 was relegated to the factory museum after the outbreak of war. Together the two projects cost Daimler-Benz the better part of 1,300,000 RM, yet had yielded little that they could then publicize and draw advantage from. Given these programs were undertaken during the major phase of re-armament, and their development pushed forward despite major shortages in the materials these projects needed suggests the government treated them as a priority. Consumption, however, was indicative of Grand Prix racing in general. At a time when fuel, rubber and exotic metals were precious commodities, the Silver Arrows consumed them at an enormous rate. As racing became increasingly more political in nature, individual victories against rivals benefited the government by fulfilling the claim of German superiority, while the participating company could no longer capitalize on the prestige generated by the victory.This explains, in part, why Kissel and Daimler-Benz were trying to convince the government to reimburse them for their huge expenditure. There were other reasons for Daimler-Benz to be interested in conducting projects for the government, though, and for them to undertake these expenses.

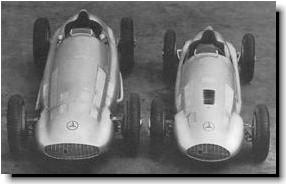

Though it would seem slipping a smaller motor into the successful W154 (on left) chassis would have sufficed, the side-by-side scale shows the level of detail undertaken to scale down and lighten the W165 (on right)

Again, the companies had been forced into a difficult position. In order to maintain credibility, both would continue to race. At the same time, racing was not producing the desired effects, or in fact the effects it had only years previous. The result was more extreme measures in the case of Daimler-Benz. At Auto Union, where setbacks had delayed the new 3-liter race car and the death of Rosemeyer had ended years of record breaking, the development of the 1.5 liter W165 Mercedes-Benz was cause for great concern. Auto Union immediately set to designing its own 1.5-liter car, though development at this point was hampered not only by lack of budget and resources devoted to the 3-liter car, but also the company was months behind Daimler-Benz. To Auto Union, this was a deliberate measure that had been taken by Daimler-Benz in order to gain an advantage:

“I am provisionally not entirely clear what reasons cause MB (Mercedes-Benz) to develop a 1.5 liter race car right now. Under such mysterious circumstances, but since at MB one of the key drivers of all actions is the competition against the Auto Union, it may be assumed that here essentially a desire for moderate prestige and moderate developmental advantages over Auto Union was relevant.”

There were also limitations to the design of the Auto Unions, who had fully developed the mid-engine platform in their Type A through C Grand Prix cars; though not a completely original design by itself, it was certainly advanced for its time and in some cases too far advanced for its drivers. Traditional Grand Prix cars, and notably Mercedes-Benz, opted for a front engine/rear drive layout for the car, which made the driving more predictable, though ultimately the car was not as well balanced as the Auto Union. Despite problems with drivers unable to utilize the cutting edge design, the Auto Union, and particularly Werner, felt that public identification of the unique mid/rear engine Auto Union was important enough to continue the design in the new 3-Liter car. This also held true for the proposed 1.5-Liter car; in a discussion over whether the car should be a front or rear engine layout, Werner stressed that the car must continue the rear engine design trend of the Auto Unions:

“In particular, the advantages and disadvantages of the car with rear- or front-mounted engine are discussed in detail. Mr. Werner Director decides that the car be constructed with rear-engine configuration- as before.”

For Werner, it was not a question of the best performance, it was a question of distinctness for marketing. Here was a distinct case of where the company may have compromised performance in order to maintain its marketability and recognition through distinctiveness from its competitors.

Daimler-Benz, for its part, also feared developments at Auto Union, particularly when it came to the T80. In a 1936 memo regarding the T80 development, the document noted that:

“Dr. Porsche also wrote explicitly requiring further knowledge of technical, structural and fabrication details of our “DB 601 “. It is the acute danger in this that the AUTO UNION is strongly interested in their own aircraft engine development.”

As it had been in the beginning, fear of the competition continued to spur developments at both Auto Union and Daimler-Benz.

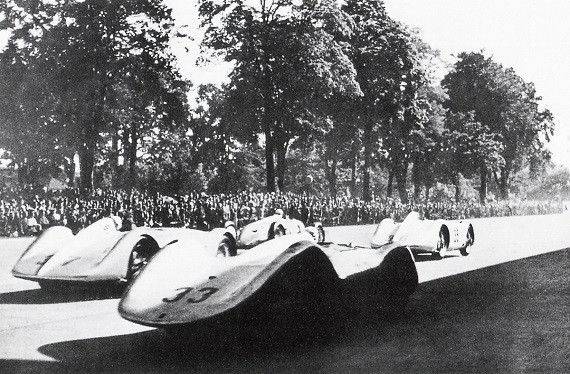

Streamliners from Auto Union (Type C, foreground) and Mercedes-Benz (W25) flank a Auto Union Type C in the 1937 Avus Race

END PART 4

-Carter

Great history piece – thank you for posting it.

Thanks Walter, two parts to go over the next two Mondays! Tune in!